For English scroll down

دُعيتُ للحديث في بودكاست (عن الاستشراق) من منصة (مجتمع)، مع المُضيف ياسين عدنان، حيثُ تحدّثتُ عن الاستشراق الهولندي من القرن السادس عشر وحتى يومنا هذا. وجدتُ نفسي أتحدث عن المخطوطات القديمة وعلماء اللغة في الجامعات الهولندية، بالإضافة إلى الطرق العديدة التي اتجهت بها هولندا نحو الشرق على مرّ القرون. كانت فرصةً رائعةً للتأمل في التعددية الثقافية والتواصل بين الثقافات، بالإضافة إلى تاريخ هولندا والشرق عمومًا.

المدرسة الهولندية في الاستشراق

عدنان: أعزائي، عزيزاتي، أهلاً وسهلاً ومرحبًا. تعتبر المدرسة الهولندية واحدة من أهم مدارس الاستشراق الكلاسيكي التي لعبت دورًا رائدًا في مجال الدراسات العربية منذ القرن السابع عشر، خصوصًا بعد إنشاء جامعة لايدن سنة 1575 ميلاديًا، وتأسيس كرسي اللغة العربية بها سنة 1613، إضافة إلى إنشاء مطبعة عربية هناك بشكل مبكر سنة 1683.

ومع ذلك، فقد عانى الاستشراق الهولندي من الإهمال من طرف الباحثين العرب، والدراسات التي كُتبت عنه باللغة العربية حتى الآن نادرة محدودة. لأجل ذلك، سنحاول اليوم تسليط بعض الضوء على المدرسة الاستشراقية الهولندية. ولقد دعونا إلى هذا اللقاء الباحثة والأكاديمية الهولندية ديزيريه كوسترز، خريجة الجامعة الكاثوليكية في لوفان في تخصص الدراسات العربية الإسلامية، مديرة مؤسسة إيوانا للتفاهم الثقافي. ديزيريه، أهلاً وسهلاً بك.

ديزيريه: مرحبًا، شكرًا جزيلًا على الدعوة. أنا سعيدة جدًا لأنني هنا معكم.

عدنان: وأنا أسعد. وأحب أن أبدأ معك بمفارقة، حضور اللغة العربية في هولندا لعله كان أسبق من حضور الهولندية نفسها. توماس أربينيوس، وهو أول أستاذ للعربية في ليدن، كان قد ألقى خطابًا افتتاحيًا عن تفوق اللغة العربية ومنزلتها الرفيعة يوم 14 مايو 1613، أي قبل قرنين تقريبًا قبل أن تكون هناك لغة هولندية. فاللغة الهولندية لم تظهر إلا مع نهاية القرن الثامن عشر. ما رأيك في هذه المفارقة؟

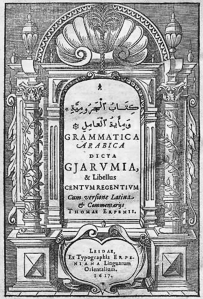

ديزيريه: شكرًا مجددًا على الدعوة وأرحب بكل المستمعين والمستمعات. بالطبع، اللغة الهولندية كانت موجودة في هولندا، لكنها لم تكن لغة أكاديمية أو لغة النخبة، لنقل. كانت اللغة الهولندية منتشرة ولكنها لم تكن موحدة. وبالفعل، توماس أربينيوس شدد على أهمية اللغة العربية. ولم يكن هو أول أستاذ للغة العربية في هولندا، لكنه كان أول من تولى الكرسي مثلما تفضلت في سنة 1613.

اللغة الهولندية أصبحت لغة موحدة في هولندا في فترة الإصلاح البروتستانتي، وأيضًا عندما ارتبطت اللغة الهولندية بالقومية الهولندية أو تطوير القومية الهولندية في إطار الحرب مع إسبانيا، حرب استقلال هولندا. اعتبرت اللغة العربية مهمة بالنسبة لهدف لاهوتي، ربما سنتحدث أكثر عنه في ما بعد، وأيضًا بسبب بداية العلاقات بين جمهورية هولندا ودول الشرق أو الدول العربية.

أربينيوس

عدنان: الدول العربية، يمكن أن نبدأ بالمغرب. حتى ونحن نتحدث عن أربينيوس، لا ننسى الحجري في المقابل في المغرب، السفير المغربي.

ديزيريه: تمام. يعني، من الممكن أيضًا أن يتساءل المرء كيف أن شخصية مثل أربينيوس، الذي عاش في أواخر القرن السادس عشر، تعلم اللغة العربية أصلًا، فلم تكن هناك الكثير من المواد لتعليم اللغة العربية. فأربينيوس على سبيل المثال، قبل أن يصبح أستاذًا للغة العربية، سافر إلى عدة بلدان أوروبية، منها فرنسا، وهناك تعرف على شخصية مغربية كان اسمه أحمد بن قاسم الحجري، وهو كان موريسكو (أي من المسلمين الذين اعتنقوا المسيحية قسرًا في الأندلس). وكان هناك مبعوث من المغرب. فطوروا صداقة، وبعد ذلك عندما رجع أربينيوس إلى هولندا وأصبح أستاذًا، تلقى رسالة من الحجري أنه سيزور هولندا. بفضل هذه الصداقة، ظل الحجري ضيفًا عند أربينيوس في هولندا طوال صيف عام 1613. وبالفعل، ساعد أربينيوس بتطوير المعجم الخاص به، وكان هناك أيضًا جدال بينهما حول الدين ومواضيع مختلفة.

عدنان: وكان هذا الجانب أيضًا الذي تفضلتِ بالإشارة إليه، هو أن هناك طبعًا قومية هولندية مقابل الإسبان. الهولنديون كبروتستانت مقابل الكاثوليكية في إسبانيا. هل ربما هذا ما قاد الهولنديين في لحظة ما باتجاه المغاربة، باعتبار أن إسبانيا كانت عدوًا مشتركًا لهما معًا؟

ديزيريه: نعم، لنبدأ من البداية. يمكننا أن نقول أن الاستشراق الهولندي بدأ في أواخر القرن السادس عشر، وهذه كانت فترة عاشتها هولندا في حرب الاستقلال مع إسبانيا الكاثوليكية، التي كانت مستعمرة لهولندا. فكانت هناك في حرب استقلال، وفي هذه الحرب كان البُعد البروتستانتي مهمًا بالنسبة لما أصبحت فيما بعد جمهورية هولندا، لأن ذلك كان شيئًا يميز هولندا عن إسبانيا الكاثوليكية. فطبعًا، كان أول المستشرقين من اللاهوتيين،

وتم النظر إلى الدين الإسلامي على أنه أفضل من الكاثوليكيين، فكانت جمهورية هولندا اتبعت سياسة “عدو عدوي صديقي”، بمعنى أن عدو إسبانيا كان المغرب والإمبراطورية العثمانية، فطوروا علاقات معهم. وبالمناسبة، فإن فترة حرب الاستقلال التي ظلّت ثمانين عامًا، كانت أيضًا تتزامن تقريبًا مع العصر الذهبي لجمهورية هولندا، حيث طورت جمهورية هولندا الكثير من العلاقات مع الشرق. وكانت المغرب أول بلد عملت معه معاهدة تجارية مع هولندا، في سنة 1609.

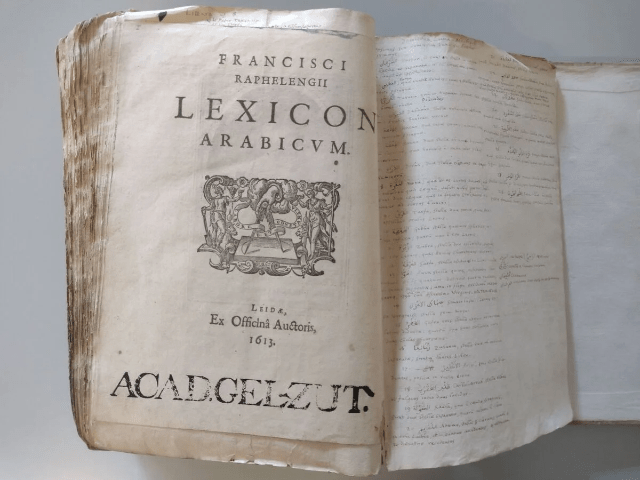

Deventer, Athenaeum Library, 100 A 4 KL, Title page F. Raphelengius, Lexicon Arabicum (Leiden, 1613): source / ديفينتر، مكتبة أثينيوم، 100 A 4 KL، صفحة العنوان رافلينيوس، المعجم العربي (ليدن، 1613): المصدر

فرانسيسكوس رافلينيوس

عدنان: وأنتِ تشيرين إلى العمق اللاهوتي ربما لهذا الحوار. أنا أفكر أيضًا أنه حتى بالنسبة للغة العربية، بمعنى من المعاني، كان اللاهوتي دائمًا يتحكم. وهناك من يقول: إن ما حصل مع اللغة العربية في هولندا لا يختلف كثيرًا عمّا حصل معها في ألمانيا. لم يتم الاهتمام بها في البداية لذاتها، وإنما تمت دراستها بسبب معجميتها القوية ونحوها الدقيق، وذلك من أجل توفير فهم أفضل للعهد القديم. لأن لغة العهد القديم كانت منقرضة في تلك الفترة، فالعبرية التوراتية كانت تعتبر ضمن اللغات المنقرضة. وإلا، هل كان من قبيل الصدفة أن أول أستاذ كرسي للعربية في جامعة لايدن كان هو نفسه فرانسيسكوس رافلينغيوس، أستاذ كرسي العبرية بالجامعة؟

عدنان: أنا أخطأت في الاسم، أليس كذلك؟

ديزيريه: تقريبًا، نعم. لأن اللاتينية كانت لغة أكاديمية في تلك الفترة. فله اسمان، “فان رافلينين” الاسم الهولندي، و”رافلينيوس”، مثل “فان إربين” و”إربينيوس”. فـ”فان رافلينين” كان أول أستاذ للغة العربية والعبرية، ولكنه لم يكن أول من تولى الكرسي للغة العربية. فهو كان أول أستاذ.

وبالفعل كان هناك علاقة وثيقة بين العبرية والعربية، كما تفضلتم. أن اللغة العبرية كانت لغة ميتة، فما كان هناك معجم كافٍ لنستند عليه لفهم العهد القديم أو الكتاب المقدس، فسموا اللغة العربية بنت اللغة العبرية.

عدنان: نعم، هناك من سمى اللغة العربية أيضًا “خادمة اللاهوت”.

ديزيريه: خادمة اللاهوت، بسبب قربها من اللغة العبرية. فبالفعل كان الاهتمام باللغة العربية في البداية اهتمامًا لاهوتيًا، لكي يستخدموها في زيادة الفهم بالكتاب المقدس. وطبعًا، كان ذلك في إطار الإصلاح البروتستانتي، وهي حركة دعت إلى إعادة قراءة النصوص. ولذلك كان هناك اهتمام جديد بقراءتها وأيضًا بفهمها. عبر لغات سامية عمومًا، مثل العربية والآرامية والسريانية، هذه هي اللغات، وطبعًا أيضًا في إطار الحركة الإنسانية “الهيومانزم” التي كان يوجد لها مركز في لايدن في هولندا.

عدنان: تمامًا، إذًا هناك هذا الجانب الإصلاحي البروتستانتي، وهناك أيضًا الجانب إذا شئنا أن نقول “التنويري”، لأن رياح التنوير بدأت تهب على أوروبا حينها. وهنا لا يمكنني إلا أن أذكر أدريان ريلاند، حتى رافلينيوس لا يجب أن ينسينا هذا الاسم. ما هي الأدوار التي لعبها أدريان ريلاند في غمرة التحولات التي عرفها المنهج الاستشراقي في سياق رياح التنوير التي بدأت تهب؟

ديزيريه: التنوير هو أيضًا سياق حيث أصبح الاهتمام بالشرق أكثر، بينما كان في البداية الاهتمام باللغة العربية من أجل أهداف لاهوتية، أصبح لاحقًا أيضًا لفهم الإسلام وفهم العربية أكثر من أجل التجارة مع الشرق. فزادت الاهتمامات، وأيضًا بسبب المخطوطات، المستشرقون الهولنديون لاحظوا أنه يوجد كثير من العلم في المخطوطات العربية، فكان هناك اهتمام بالأدب والثقافة، وكافّة الأشياء.

فأدريان ريلاند كان أحد أول المستشرقين المبكرين في هولندا، عاش في أواخر القرن السابع عشر، وكان أستاذًا للغة العربية في أوتيركس. وكتب أحد أهم الكتب التي أثرت على رؤية الهولنديين تجاه الإسلام. والعجيب أنه لم يسافر ولا مرة، ولم يخرج من هولندا أبدًا، فكل ذلك كان بناءً على مصادر أولية. فصدر الكتاب المهم هذا الذي اسمه: “في الأديان المحمدية”، والذي صدر في عام 1705. وكان هذا الكتاب مهمًا لعدة أسباب: أولًا، دعا إلى الرجوع أو العودة إلى مصادر أولية لفهم الدين الإسلامي، وثانيًا، أصر على أهمية تعليم اللغة العربية لفهم الإسلام أو الدين الآخر في هذه الحالة.

وكتاب ريلانت هذا منقسم إلى جزءين: في الجزء الأول، يعالج أو يترجم العقيدة الإسلامية إلى اللغة اللاتينية، وكتب ملاحظات تشرح للقارئ الهولندي حول الدين الإسلامي. وفي الجزء الثاني، وصف ثمانية وثلاثين فكرة خاطئة حول الإسلام منتشرة وقتها في هولندا، ووصف لماذا كان ذلك خطأ، بالطبع.

عدنان: هل يمكن أن نقول بأن ذلك كان، بمعنى من المعاني، يسجل ضد الكاثوليك الإسبان؟

ديزيريه: يمكن.

عدنان: لأن أغلب تلك الأفكار نشأت في بيئة كاثوليكية، خصوصًا بعد طرد المسلمين من الأندلس.

ديزيريه: وتم منع كتابه حتى من قبل البابا في روما، واتهم بالكلفينية التركية، وهذا هو الشيء الذي كان الكاثوليك يقولون عنه، أن البروتستانت قريبون جدًا من الأتراك، لدرجة أنهم كانوا يعملون دعاية لصالح العثمانيين في وقتها. ولكن أعتقد أنه فعلاً حاول أن يكون موضوعيًا في بحثه.

التحول في أدوار اللغة العربية بالنسبة للهولنديين

عدنان: هذا الاهتمام، كما قلنا، باللغة العربية. نحن نعرف أن المجتمع الهولندي بشكل عام حريص على عدم إنفاق المال العام على ما لا ينفع. يعني، الهولنديون معروفون بهذه الخاصية، وكانوا دائمًا حينما ينفقون على اللغة العربية يبررون إنفاقهم، في البداية بأن اللغة العربية “خادمة اللاهوت”. ولكن فيما بعد، كما تفضلت بالإشارة إلى هذه المعطيات كلها، كان هناك العلاقة مع العثمانيين، ثم فيما بعد، حينما وصل الهولنديون إلى منطقة جنوب شرق آسيا المسلمة في أواخر القرن السادس عشر، اكتشفوا أن اللغة العربية مفيدة في العلاقة مع هذا المجتمع، ما دام مجتمعًا إسلاميًّا. أريد أن أسألك عن هذا التحول في أدوار اللغة العربية بالنسبة للهولنديين، مجتمعًا ومستشرقين. كيف ترصدينه؟

ديزيريه: شكرًا على السؤال. أعتقد أن الاستشراق في هولندا يختلف عن جيرانه، لأنه أولًا لم يكن لديهم أي مستعمرات في البلدان العربية. هذا يختلف عن فرنسا، بالطبع. ولم يكن لديهم أي رحلات تبشيرية في البلدان العربية. فدور اللغة كان مختلفًا عن جيرانه. فكما ذكرنا في البداية، كان الاهتمام لأسباب لاهوتية، وفيما بعد للتجارة وكسب العلم من المخطوطات العربية.

وبالنسبة للفترة الاستعمارية، كانت اللغة العربية مصدرًا أو وسيلة لفهم النصوص الإسلامية المكتوبة باللغة العربية التي كانت تستخدم في إندونيسيا على سبيل المثال. فلم تكن اللغة وسيلة للتواصل مع الإندونيسيين، بل كانت أكثر لفهم النصوص. وفيما بعد، بالطبع، بعد استقلال إندونيسيا، يمكننا القول إن الاهتمام بتعليم اللغة العربية قد قل قليلاً.

وفي الفترة الأخيرة، خصوصًا بعد نقد إدوارد سعيد، صار التدريس يشمل اللهجات أكثر في الجامعات الهولندية من الفصحى. الفصحى كانت مهمة للدراسات الفيلولوجية، ولكن بعد انتقاد إدوارد سعيد، أصبحت الدراسة ليس كاستشراق، بل دراسة اللغة العربية والعلوم الإسلامية، وأصبحوا يدرسون أيضًا لهجات، لكن أعتقد حاليًا، هناك نوع من الإهمال لتدريس اللغة العربية في جامعات لايدن. وقد كان هناك خبر قبل أسبوعين في الأخبار الهولندية أن جامعة لايدن وجامعة أوترخت ربما تلغيان دراسات اللغة العربية بسبب، عدم وجود ميزانية كافية لتشجيع هذا.

ويمكننا أن نتساءل إذا كانت الجامعة هي أفضل مكان أيضًا لتعليم اللغة العربية، لأن اللغة العربية أصبحت جزءًا لا يتجزأ من المجتمع الهولندي حاليًا. هناك جاليات عربية تتحدث العربية، وهناك أجيال ثانية وثالثة من المغاربة، على سبيل المثال، تعلموا الهولندية، وكثير منهم مهتمون بتعليم اللغة العربية. ولكن ليس الكل يذهب إلى الجامعة في هولندا، هناك جزء صغير من المجتمع الهولندي يذهب إلى الجامعة. وبالتالي، تم أيضًا تدريس اللغة العربية في مدارس خارج إطار الجامعة، وأعتقد أن هذا تطور مهمّ يمكن أن ننقاشه.

عدنان: تمامًا. يعني لم تعد الجامعة هي الحضن الوحيد لتعليم اللغة، كما تفضلتي. هناك تحول من الاهتمام الأولي باللغة العربية الفصحى في عمقها الفيلولوجي ومضامينها وما إليه، إلى الانتباه للهجات، خصوصًا لهجات الجاليات التي استوطنت هولندا، ربما أفكر في الجالية المغربية على سبيل المثال.

ولكن، ألا تحسّين ديزيريه أنه بعد أحداث 11 سبتمبر، هذا الاهتمام باللغة العربية لم يعد اهتمامًا باللغة في ذاتها، وإنما عاد ليرتبط من جديد بالإسلام؟ تم ربط العربية بالإسلام في إطار -ربما- الاهتمام بالإسلام الراديكالي الذي بدأ ينتشر في أوروبا، وعبر العالم. فتم دمج الدراسات أو الكراسي العربية مع الدراسات الإسلامية في أكثر من جامعة هولندية. ما رأيك في أن الأمر يتعلق بمشروع “أسلمة” للمعرفة العربية في جامعات هولندا؟ وألا يعني هذا أن اللغة العربية عادت من جديد لتلعب دورها القديم كـ”خادمة” للاهوت؟

ديزيريه: سؤال جيد. أعتقد أنه يمكننا أن نبدأ بأن نذكر أن دراسة الاستشراق في هولندا كانت دائمًا تتبع تيارين: التيار الفيلولوجي الذي لا يزال موجودًا، والتيار التسييسيّ أو المسيس للاستشراق. هذان التياران كانا موجودين جنبًا إلى جنب، وأعتقد أنه يمكننا القول بذلك، وهناك أمثلة على ذلك. أما بالنسبة لما حدث بعد 11 سبتمبر، صحيح أن دراسة اللغة العربية ارتبطت بمواضيع سياسية أكثر، وهذا كان حتى قبل 11 سبتمبر، حيث كانت هناك انتقادات موجهة إلى الجاليات العربية في هولندا. على سبيل المثال، أهم رجل سياسي ذكر هذا كان بن فورتين، بالطبع، هذا كان قبل 11 سبتمبر. وفيما بعد 11 سبتمبر، كان هناك حادثة قتل تيو فان خوخ، وهو رجل إعلامي.

وقد أثر ذلك بشكل كبير على المجتمع الهولندي وعلى النقاش حول إمكانية اندماج الجالية العربية أو الجالية الإسلامية في هولندا. فبالطبع، بعد هذا الحادث، صار هناك نوع من تسييس الاستشراق أو تسييس دراسة اللغة العربية والعلوم الإسلامية. بمعنى أن التركيز أصبح على الإسلام الراديكالي في هولندا أو إمكانية الاندماج. كانت اللغة العربية ضرورية في هذا السياق لأن المستشرقين رجعوا إلى قراءة النصوص الإسلامية والنظر إلى هذه النصوص لتحديد مدى توافقها مع المجتمع الهولندي. وهذا كان أحد الأسئلة المطروحة في تلك الفترة. ثانيًا، كانت اللغة العربية ضرورية للتواصل مع الجاليات في هولندا التي تتحدث العربية. فكانت نوعًا ما “لغة خادمة”، ولكن لهدف آخر بالطبع.

تأثير ألف ليلة وليلة

عدنان: سنعود الآن إلى النصوص الأساسية التي انتبه لها المستشرقين الأوائل، وشكلت مادة ملهمة، ليس فقط للمستشرقين وقرائهم ومن يتابعون إنتاجاتهم، ولكن حتى للسياسيين. أفكر مثلًا في الترجمة الفرنسية لأنطوان غالاند لألف ليلة وليلة، لا أدري أين قرأت أن الترجمة الهولندية لعلها صدرت قبل ترجمة أنطوان غالاند، ولكن فيما نلاحظ بأن الترجمة الفرنسية لألف ليلة وليلة كان لها تأثير كبير في فرنسا وعبر أوروبا كلها وعبر العالم. بينما نحس بأن الترجمة الهولندية لم يكن لها نفس التأثير. هل لديك تفسير لذلك؟

ديزيريه: نعم، حول معلومة أن الترجمة الهولندية كانت قبل الفرنسية لم أجد هذه المعلومة. لكن أول ترجمة أو أول جزء ترجم من قبل جالاند كان في 1704. وأعرف أنه في هولندا كانت هناك نسخة فرنسية مقرصنة من هذا الكتاب، ظهرت بعد هذه الترجمة بسنة.

عدنان: ظهرت بالفرنسية؟

ديزيريه: بالفرنسية ولكن كنسخة مقرصنة. فكانت موجودة عند النخبة الهولندية، لأنه كما ذكرنا، اللغة الهولندية لم تكن دارجة في وقتها. لكن الكل كان يقرأ، خصوصًا النخبة كانت تقرأ ألف ليلة وليلة، لكن لم يتلقَ الكتاب نفس الحماس كما في فرنسا. كان له تأثير، ولكن ليس نفس التأثير…

عدنان: هل يمكن، مثلاً، أن نفسر عدم التأثير إلى ذلك الحد بمسألة العقلية؟ عقلية الهولندي التي تختلف عن عقلية الفرنسي أو البريطاني مثلاً؟

ديزيريه: نعم، هناك تفسير بأن العقلية الكالفينية الهولندية كانت أقل ميلاً إلى حكايات الطرفة أو الفكاهة، مثلما اعتُبرت ألف ليلة وليلة. وكانوا أكثر ميلاً إلى حكايات الحِكَم. على سبيل المثال، حكاية حي بن يقظان.

عدنان: ابن طفيل.

ديزيريه: نعم، ابن طفيل.

عدنان: ابن طفيل تمت استعادة حكاياته في الأدب الهولندي.

ديزيريه: صحيح، حي بن يقظان ترجم ثلاث مرات. أول مرة في سنة 1672، وبعد ذلك مرة أخرى في 1710. وفي هذه النسخة الأخيرة كتب أدريان ريلانت الذي ذكرناه ملاحظات تشرح للقارئ الهولندي حول أحداث حي بن يقظان.

عدنان: وفلسفة ابن طفيل أيضًا، لأنها رؤية فلسفية.

Frontispiece of De natuurlyke wysgeer, of het Leven van Hai ebn Jokdan, Rotterdam, by Pieter Van der Veer, 1701, Courtesy Leiden University Libraries, 841 F 23 source / واجهة الكتاب (حي إبن يقظان)، روتردام، بقلم بيتر فان دير فير، 1701، بإذن من مكتبات جامعة ليدن، 841 ف 23 المصدر

ديزيريه: وجزء من العقل الكالفيني أنهم كانوا مهتمين أكثر بالبعد الديالكتيكي من البعد الصوفي في كتاب ابن طفيل على سبيل المثال. ولكن رغم ذلك، ألهمت ألف ليلة وليلة عدة كتّاب هولنديين لكتابة ما نسميه حكايات شرقية. أحد أشهر هؤلاء الكتاب هو يان نومانس الذي كتب مسرحيات على نفس وتيرة ألف ليلة وليلة.

عدنان: عجيب، إذن، ومع ذلك، هناك تأثير. إذًا، سنحترم جدية العقلية الهولندية ونذهب إلى الجامعة مباشرة. جامعة لايدن التي بدأت بها الدراسات الاستشراقية سنة 1591، المعهد الهولندي للشرق الأدنى التابع لها تأسس سنة 1939. أنا أريد أن أسائل تلقيك للدراسات الاستشراقية في جامعة لايدن. هل تتلقين هذا الحقل كحقل أكاديمي محض، أم ربما كظاهرة سوسيوسياسية؟

ديزيريه: أعتقد أن مسار جامعة لايدن، وخصوصًا تعليم الاستشراق فيها، كان دائمًا متأثرًا بالسياق الاجتماعي أو السياسي. فحتى بداية جامعة لايدن، والقصة بالطبع أنها تأسست كهدية من فيليم فان أورانيا، وهو الذي قاد الحرب ضد الإسبانيين لمدينة لايدن بسبب مقاومة مدينة لايدن. بسبب مقاومة المدينة ضد الإسبانيين. فمن البداية كانت الجامعة هدية تلقائيًّا في سياق سياسي اجتماعي. بعد ذلك، يمكننا أن نرى، مثلًا، أن كثيرًا من المستشرقين المبكرين كان لهم دور في ترجمة رسائل تجارية لشركة الهند…

عدنان: الصينية؟

ديزيريه: الصينية، نعم. وفي فترة الاستعمار، كان هناك ارتباط وثيق بين الجامعة وإندونيسيا. دروس حول إندونيسيا، أو دروس حول الإسلام في إندونيسيا. الشخصية البارزة التي ساهمت في ذلك كانت كريستيان سنوك هورخرونيه. وكما ذكرنا بعد أحداث 11 سبتمبر، كثير من العلماء في لايدن درسوا الإسلام الراديكالي ومواضيع أخرى مرتبطة بالسياق.

ولكن في نفس الوقت، هناك دائمًا التقاليد الفيلولوجية في جامعة لايدن، والمعهد الذي ذكرته مثال على ذلك. فهناك معاهد تهتم بدراسة المخطوطات الموجودة في جامعة لايدن. وبالمناسبة، أحب أن أذكر أن جامعة لايدن، من بين كل الجامعات في هولندا، كان لها دور كبير في تحديد أو في تشكيل دراسة الاستشراق، ليس فقط في هولندا، ولكن في أوروبا بشكل عام. وأعتقد أنه يمكن تقسيم ذلك إلى ثلاثة أشياء. أولًا: تأثير المستشرقين الذين خرجوا أو عملوا في جامعة لايدن، بدءًا من أربينيوس وصولًا إلى خوليوس، أو شخصيات أخرى مثل رينهارت دوزيه، وأيضًا يانج بول. كل ذلك أدى إلى منهج جامعة لايدن المتخصص في تحليل النصوص بدقة. فأعتقد هذا أولًا. ثانيًا: المخطوطات الموجودة في جامعة لايدن. لا توجد جامعة في العالم، أو في أوروبا على الأقل، لديها هذه الكمية من المخطوطات.

عدنان: أنا زُرتها واستمتعتُ بقضاء يوم كامل بين المخطوطات العربية هناك.

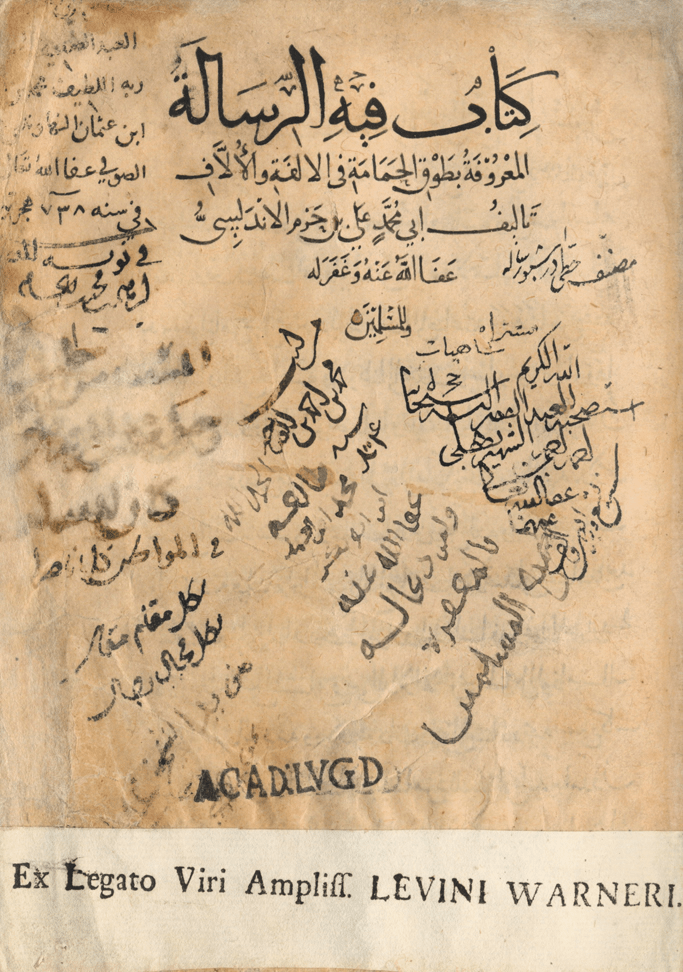

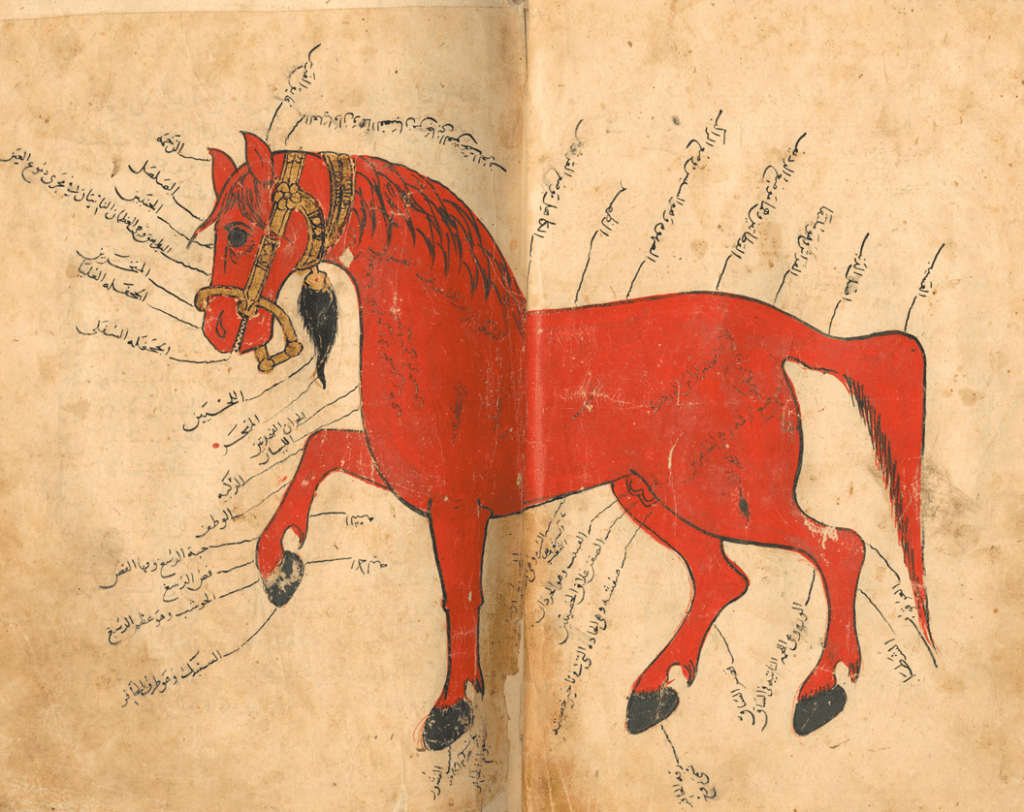

ديزيريه: نعم، جميل. هناك مجموعتان أساسيتان. الأولى من ياكوب خوليوس، وهو كان خليفة أربينيوس، وجمع المخطوطات في المغرب بمساعدة الحجري الذي ذكرناه سابقًا، وأيضًا في القسطنطينية وحلب. فهو جمع أكثر من –أتصور- 400 مخطوطة. ولكن أكبر مجموعة أتت شخص اسمه ليفينوس فارنر، وهو كان مبعوثًا هولنديًا في القسطنطينية، وعاش هناك فترة طويلة. وبمساعدة شبكته، كانت هوايته أن يجمع المخطوطات، فجمع أكثر من ألف مخطوطة. فهذا أمر رائع جدًا، وتبرع بالمخطوطات لجامعة لايدن بعد وفاته. وهنا نجد على سبيل المثال “طوق الحمامة” لابن حزم، النسخة الوحيدة منه موجودة في جامعة لايدن، وقد جاءت من ليفينيوس فارنر. وأيضًا مثلًا، أحد مجلدات الطبري موجود في لايدن. وهذا شيء يفتخر به، والآن يعملون على رقمنة كل هذه المخطوطات.

دار نشر بريل

عدنان: ونحن نتحدث عن المخطوطات، نتحدث أيضًا عن طباعة الكتب العربية. وهنا يجب أن نتحدث عن دار نشر “بريل” بلايدن، دار النشر الهولندية العريقة التي تأسست سنة 1683، والتي تعتبر دارًا استثنائية بكل المقاييس. فقبل دخول المطبعة إلى العالم العربي، كانت “بريل” قد شرعت في استلام المخطوطات العربية مباشرة بعد تحقيقها لطباعتها بالحرف العربي. ويكفي أن نذكر بطباعة “بريل” لدائرة المعارف الإسلامية والأطالس التراثية الخاصة ببلاد العرب والمسلمين. لا يمكن أن نتحدث عن جامعة لايدن هنا ولا نتحدث عن دار نشر “بريل”.

ديزيريه: نعم، دار نشر “بريل” كان لها دور كبير في طبع الكتب للمستشرقين الهولنديين، ابتداءً مع إربينيوس، وطبعًا فيما بعد، الكثير من المستشرقين طبعوا (أعمالهم) هناك، لأنهم كانوا محترفين جدًا في طباعة المخطوطات أو الخطوط غير الغربية.

عدنان: اللاتيني.

ديزيريه: نعم اللاتيني، مثل العربية والسنسكريتية والعبرية ولغات أخرى. أهم مشروعين أحب أن أذكرهما: أولًا، تاريخ الطبري، الذي كان إنجازًا كبيرًا بالنسبة لدار نشر “بريل”. وأحد مخطوطات تاريخ الطبري كان موجودًا في جامعة لايدن، وكان المستشرق “دغوي” هو الذي تبنى المشروع لكي يطبع التاريخ الكامل للطبري في دار نشر “بريل”. فهو عمل مع مستشرقين من دول مختلفة في العالم لكي يجمع المجلدات، أعتقد أنها كانت عشرين مجلدًا للطبري ليعمل منها كتابًا كاملًا. فهذا كان أحد المشاريع الكبيرة لـ”بريل”، وطبعًا الموسوعة…

عدنان: الموسوعة الشهيرة…

ديزيريه: الشهيرة، نعم. فدار نشر “بريل” بدأت بنشر هذه الموسوعة في أواخر القرن التاسع عشر، وطبعًا كانت جهدًا كبيرًا.. موسوعة بهذا الحجم، وكان تعاون كبير.. في النسخة الأولى ساهم فيها مستشرقون أوربيون. وكان هناك انتقاد من العالم العربي فيما بعد، أنه لم يوجد أي متخصصين من العالم العربي أو مسلمين ساهموا في الموسوعة. فحاولوا أن يغيروا ذلك في النسخة الثانية، والآن حاليًا يعملون على النسخة الثالثة من الموسوعة.

عدنان: لا ننسى أننا حينما نتحدث عن بداية المطبعة في 1683، لم يكن هناك طبع في العالم العربي. فهي أول مطبعة عربية، لها الريادة عربيا، وليس فقط عبر العالم. لهذا نلح على أهميتها حتى بالنسبة لنا، وليس فقط بالنسبة لهولندا أو جامعة لايدن.

ديزيريه: نعم، نعم. والآن، يعملون كثيرًا، مازالوا يطبعون الكتب، وأيضًا بشكل افتراضي. على موقعهم يمكنك العثور على الكثير من المجلات والكتب. وكان لديهم حتى عام 2006 مكتبة في مركز مدينة لايدن حيث باعوا الكتب، لكن للأسف أغلقت أبوابها.

عدنان: كالكثير من المكتبات العلمية المتخصصة.

ديزيريه: ممكن بالطبع تفسير ذلك بأن الدراسة الفيلولوجية خسرت أهمية في مجال الدراسات الاستشراقية.

عدنان: تمامًا، هي فعلاً خسارة. ولكن مع ذلك، ما زالت المكتبة متوفرة. وسأخبرك أنني قبل يومين تلقيت عبر الإيميل برنامج ندوة في إيطاليا، ندوة تضم مجموعة من المهتمين بالثقافة العربية والإسلامية. هناك ندوة كبرى حول الثقافة والأدب في المغرب في إيطاليا، وفي الرسالة التي تلقيتها، يشيرون إلى أن أعمال الندوة ستصدر عن مطبعة “بريل”.

ديزيريه: جميل جدا.

عائلة يونبول

عدنان: بما أنها نسخة افتراضية، ولكنها ما زالت قيد النشر والطباعة الافتراضية والإلكترونية على الأقل. هناك معْلمة أخرى من معالم الاستشراق الهولندي في الواقع. إلى جانب الجامعة والمطبعة، هناك عائلة “يونبول”. هذه العائلة التي تعتبر أشهر عائلة استشراقية ليس فقط في هولندا، بل ربما في كل أوروبا. كيف ترصدين، ديزيريه، المسار الاستشراقي لهذه العائلة الذي انطلق خلال النصف الأول من القرن التاسع عشر وانتهى بوفاة جوتييه يونبول في 2010؟

ديزيريه: نعم، هذه العائلة كان لديها دور مهم في ترسيخ الدراسة الاستشراقية في هولندا. فنجد أن الأول من الأجيال الأربعة كان ثيودور يونبول، وهو كان فعلاً شخصًا تخصص في الشريعة الإسلامية، وهو من أسس هذه الدراسة أو ساهم بشكل كبير في منهجية دراسات الشريعة الإسلامية في هولندا.

وابنه أبراهام، درّس في المعهد الموظفين الهولنديين لإندونيسيا، ودرّس هناك من بين مواضيع أخرى اللغة اليافانية (يافانز). فممكن أن نقول إنه من الجيل الأول إلى الثاني نشاهد أن أبراهام كان له علاقة بأهداف دولة هولندا، وابن لأبراهام. الآن ننتقل إلى..

عدنان: الجيل الثالث.

ديزيريه: الجيل الثالث، اسمه أيضًا ثيودور. كتب كتابًا مهمًا جدًا بالنسبة لتعليم الموظفين الهولنديين في إندونيسيا، كتابًا حول “الشريعة المحمدية”. في وقتها كانوا يسمونها “الشريعة المحمدية”، في 1903. وهذا الكتاب ظل لعقود طويلة المرجع للموظفين في إندونيسيا.

عدنان: الموظفين الهولنديين الذين يعملون في إندونيسيا خلال فترة استعمار هولندا لإندونيسيا.

ديزيريه: نعم، صحيح. وطبعًا بعد استقلال إندونيسيا، عمومًا، قل الاهتمام الهولندي بدراسات الاستشراق، لأنه لم يكن هناك أفق للعمل في إندونيسيا. وبالتالي، كان هناك اهتمام أقل بدراسة الاستشراق. وهنا نجد أنه كانت هناك مساحة أكبر لمواضيع فيلولوجية من جديد.

فآخر الأجيال، جوتييه، كان مستشرقًا فيلولوجيًا بامتياز، بمعنى أنه كان مختصًا بالحديث، وكان شغوفًا جدًا بهذا الموضوع. كتب كتابه حول موسوعة الأحاديث النبوية أو الأحاديث الصحيحة. صدر الكتاب في 2007. وأنا سمعت من زملائه في جامعة لايدن أنه كل صباح كان يذهب إلى مكتبة الكتب الشرقية في لايدن ويدرس الأحاديث والإسناد، وكان شغوفًا جدًا بهذا الموضوع. ساعات طويلة، كان عنده نفس طويل بالنسبة للموضوع.

عدنان: ولكن هذا النفس سينقطع في 2010 بعد وفاة جوتييه ورحيله. لحسن الحظ أن كل تراث العائلة لم يضِع، لأن الأرشيف والمخطوطات كلها أُعطيت لجامعة لايدن. وأنا اطلعت على بعض هذا الأرشيف هناك. ثم أيضًا هناك المؤسسة، مؤسسة يونبول، التي تهدف اليوم إلى تعزيز دراسة اللغة العربية والإسلام. هل تعتقدين أن هذه المؤسسة تشكل بمعنى من المعاني امتدادًا لعطاء هذه الأجيال الأربعة؟

ديزيريه: نعم بكل تأكيد، لأن المؤسسة تدعم باحثين من كل أنحاء العالم ليستمروا في الدراسة الفيلولوجية في جامعة لايدن. وأعتقد أن هذا مهم جدًا.

Ring of the Dove (Ṭawq al-ḥamāma fī ‘al-ulfa wa-al-ullīf) by Ibn Hazm, work written around 1022 CE in Játiva, south of Valencia. This manuscript was copied in 1338 most probably in Syria or Egypt. Manuscript since 17th century in Leiden University Library, The Netherlands. Or.927, fol.1a. Ex libris Levinus Warner (“Ex legato viri ampliss. Levini Warneri”): source / طوق الحمامة في الألفة والليف لابن حزم، كُتب حوالي عام ١٠٢٢ ميلادي في ياطيفا، جنوب فالنسيا. نُسخت هذه المخطوطة عام ١٣٣٨، على الأرجح في سوريا أو مصر. مخطوطة تعود إلى القرن السابع عشر في مكتبة جامعة لايدن، هولندا. تاريخها: ٩٢٧، الصفحة ١أ. من مكتبة ليفينوس وارنر (“إكس ليغاتو فيري أمبليس. ليفيني وارنر”): المصدر /

رينهارت دوزيه

عدنان: تمامًا. إذن هل تعتقدين أنه يمكننا إنهاء حديثنا دون أن نتوقف عند معلم آخر من معالم الاستشراق الهولندي؟ أفكر في رينهارت دوزيه، رائد الدراسات الأندلسية، الذي لم يكن لا عربيًا ولا إسبانيًا، ومع ذلك هو صاحب أهم كتاب مرجعي حول تاريخ المسلمين في إسبانيا. ما دلالة أن يتصدى لهذا التاريخ مستشرق من خارج المدار العربي الإسباني وهولندي بالذات؟

ديزيريه: نعم، شكرًا على السؤال الجميل. طبعًا هذا الكتاب حول المسلمين في الأندلس، في إسبانيا، كان أحد أهم الكتب حول الموضوع. وأنا متأكدة أنكم ذكرتم الكتاب في أكثر من حلقة من هذا البرنامج. فأعتقد أهمية أن يكون أولًا خارج الإطار الإسباني وخارج الإطار العربي، فهو نظر إلى تاريخ المسلمين في إسبانيا بشكل أكثر حيادية. قد يكون ذلك، لأنه لا يتبع السرديات العربية التي تقول: إن الأندلس كانت الفترة المثالية، ولا يتبع السرديات الإسبانية التي..

عدنان: تعتبر إقامة المسلمين في الأندلس نكبة ومصيبة وكارثة نالت منهم ومن تاريخهم.

ديزيريه: نعم، وركز على “الريكونكويستا” أكثر من أي شيء آخر. أعتقد أنه كان باستطاعته أن ينظر إلى الموضوع بحياد أكبر. وكونه هولنديًا، كباحث مقيم في هولندا ومرتبط بجامعة لايدن، فكان الكثير من المصادر متاحًا له من المخطوطات. فكان بإمكانه أن يبحث في مصادر أولية جديدة حول الموضوع.

وطبعًا كان في السياق أيضًا أنه هناك مازال في الذاكرة الجمعية الهولندية الحرب ضد إسبانيا، فهو كان يشك في كل شيء له مصدر في إسبانيا بسبب هذا التاريخ، ثمانين عامًا تاريخ استقلال هولندا. نعم، لكن في نفس الوقت يمكننا أن نقول إنه لم يكن فقط مستشرقًا هولنديًا، لأنه كتب باللغة الفرنسية طبعًا، وأيضًا كان متأثرًا بأفكار رينو وجوبينيو. فكان ينظر إلى الأندلس أيضًا في سياق معين، حيث تأثر بالأفكار الموجودة التي أعطت أهمية كبيرة مثلًا للعرق في بحثه.

عدنان: على فكرة، أنا فعلاً سبق لي أن استحضرت دوزيه في أكثر من لقاء سابق. دائمًا أستحضره لكي أشيد بصرامته العلمية، لأن الرجل كان يؤكد أنه لا سبيل إلى إنجاز كتابة تاريخية علمية لتاريخ الأندلس إلا بعد تحقيق أهم النصوص المتعلقة بهذا التاريخ. لهذا حقق “البيان” لابن عذاري المراكشي، حقق “المعجب في تلخيص أخبار المغرب” لعبد الواحد المراكشي، حقق “نزهة المشتاق” للشريف الإدريسي، كما شرع في تحقيق “نفحة الطيب” للمقري. صرامة وطول نفس صاحبها لا يمكن إلا أن يكون إمّا ألمانيًّا أو هولنديًّا.

ديزيريه: ممكن أن يكون ذلك، ولكن أعتقد هي صرامة دوزيه أكثر من أي شيء آخر.

عدنان: تنسبينها للشخص لا للبلد.

ديزيريه: لأنه حتى قبل أن يكتب هذا الكتاب، وهذا الكتاب أخذ عشرين سنة ليكتبه، كان دقيقًا جدًا في بحثه حول المخطوطات في جامعة لايدن عندما كان ما زال طالبًا. فكتب هذا المعجم حول لباس العرب بسبب دراساته للمخطوطات، وكان فعلاً فريدًا في طول نفسه. وقرأت طرفة أنه حتى عندما تزوج في 1844، قضى رحلة شهر العسل هو وزوجته في ألمانيا. فحتى خلال رحلة شهر العسل كان يبحث عن مخطوطات. لا أعرف ما كان رأي زوجته في ذلك، ولكن في هذه الرحلة وجد مخطوطة ومصدرًا مهمًا في مدينة جوته الألمانية حول تاريخ السد الأندلسي، الذي أثّر على كتاباته.

عدنان: عجيب! وأنا أتكلم ونحن مدينون له بالتحقيقات في الواقع، الكتب التي حققها والتي جعلته فعلاً يرمّم الرؤية لتاريخ الأندلس، ويعطيه حضورا طيبا في بناء هذا التاريخ للسردية العربية. فمن هنا كان الإنصاف في الحقيقة. كان رجلاً منصفًا جدًا في بناء ذلك التاريخ وكتاباته.

كريستيان سنوك هورخرونيه

عدنان: هناك شخصية أخرى يهمني التوقف معها، لأنه بالنهاية، الاستشراق الهولندي له رموز، ونحن الآن نمُرُّ بدويزيه. أريد أن أتوقف مع هورخرونيه كريستيان سنوك؛ هورخرونيه الذي اعترف له الكثيرون بالنبوغ، ولكن في نفس الوقت هناك مواقف تُسجل على أدواره خلال فترة الاستعمار الهولندي، حتى إنه اتُّهم مباشرة بالجاسوسية. ولا أدري إلى أي حد تتفقين مع هذه التهمة؟

ديزيريه: نعم، شخصية سنوك هورخرونيه من أشهر المستشرقين الهولنديين، ومن أكثر المستشرقين الذي ثار الجدل حولهم. ليس فقط بسبب دوره كمستشرق ساهم في تطوير السياسة الاستعمارية في إندونيسيا، ولكن أيضًا بسبب رحلته إلى…

عدنان: الحج.

ديزيريه: الحج. هذه الرحلة حيث اتُّهم فيها بالجاسوسية، ولكن، أعتقد أن كلمة “جاسوس” قوية عليه، لأنه كان باحثًا أنثروبولوجيًا أكثر من أي شيء آخر. وهذا ما قام به في مكة. يعني أنه ذهب إلى هناك ليس فقط باسم الحكومة الهولندية لكي يكتب عن الجالية الإندونيسية خلال الحج. وإذا الجالية الإندونيسية لديها أفكار قومية إسلامية…

عدنان: لا، هو بالنهاية، سنوك حينما عاد من الحج، كتب تقارير، وقال للإدارة الهولندية: حاولوا أن تضايقوا الإندونيسيين لكيلا يذهبوا إلى الحج. ربما لإحساسه بأنهم يُشحنون دينيًا، وهذا ضد –ربما- مصالح الإدارة الهولندية.

ديزيريه: حسنًا، شكراً على السؤال. طبعًا، الطريقة التي قام بها ببحثه في هذه الأيام، في الوقت الحاضر، ليست مقبولة. هذا واضح بأن طريقته في القيام بالبحث مشكوك فيها. ولكن، لا نستطيع أن نقول بنسبة مئة في المئة إنه قام بالرحلة متنكرًا، لأنه كان حسب كلام نفسه مسلمًا. فكان لديه الحق ليقوم بالحج. طبعًا إذا كان فعلًا مسلمًا أم لا فقط هو يعرف. لا نستطيع أن نحكم على نيته، وكان أيضًا قد تعرض لضغط من قبل الهولنديين ألّا يكون مسلمًا، وضغوط من أطراف مختلفة. ولكنه كتب في رسائل لأصدقائه في وقت مبكر أنه اعتنق الإسلام.

عدنان: اعتنق الإسلام. وتزوج من إندونيسية، وكان له منها أربعة أبناء.

ديزيريه: فإذا كان في الرحلة متنكرًا أم لا، فهذا سؤال. بالنسبة لدراسته حول الإندونيسيين في داخل…

عدنان: الحج.

ديزيريه: خلال الحج، الحكومة الهولندية وكّلته بأن يعمل هذا البحث. وهذا البحث أدّى إلى أول كتاب كامل حول الحياة في مكة للهولنديين. كان أول كتاب سمح للهولنديين أن يفهموا أيضًا طريقة الحياة في مكة. فكان له تأثير جيد أيضًا بالنسبة للصورة حول المسلمين وحول الحج. فكان له أيضًا تأثير، نوعًا ما، إيجابي ضد الصورة النمطية. فالموضوع ليس أبيض أو أسود.

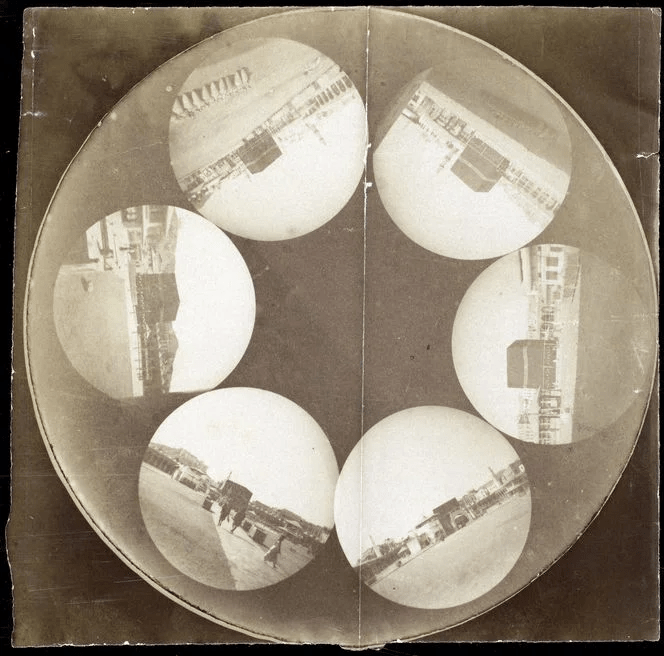

Sound fragment from the Hijaz made on wax cylinders in 1909, commissioned by Snouck. Music / مقطع صوتي من الحجاز، أُنتج على أسطوانات شمعية عام ١٩٠٩، بتكليف من سنوك. موسيقى

عدنان: أبدا، أبدا. ليس أبيض أو أسود. ونحن هنا فعلاً لتدارس هذه الأوجه في تداخلها. طبعًا. من الطبيعي أن تتداخل الأمور المعرفية مع المصالح المتعددة والمتضاربة أحيانًا.

ديزيريه: أريد أن أذكر شيئًا، مثلاً، سنوك هورخرونيه، كان أول شخص عمل على تصوير مكة، والحياة اليومية في مكة، خصوصًا بالتركيز على الإندونيسيين. وحتى إنّه قام بتسجيل الآذان في مكة. فهو من أول الأشخاص الأنثروبولوجيين الذين قاموا ببحث، ليس فقط كتابة، ولكن أيضًا تصوير وتسجيل. فعندما ترى الصور الآن، ترى أنه قام بشيء جميل أيضًا.

Secret recording Snouck made in Mecca with a tiny camera that fit in a buttonhole. With the camera, the Dutchman took six photos of the Kaaba, the central shrine of Islam in the Grand Mosque in Mecca: source / سجل سنوك تسجيلًا سريًا في مكة المكرمة بكاميرا صغيرة تُثبّت في عروة زر. التقط الهولندي بهذه الكاميرا ست صور للكعبة المشرفة، المقام المركزي للإسلام في المسجد الحرام بمكة المكرمة: المصدر /

عدنان: تمامًا، ومذهل ومهم معرفيًّا

ديزيريه: الموضوع قليلًا…

عدنان: تمامًا، بالغ التعقيد. وأنا أغبطه لأنه كان له محامية رفيعة. أنتِ تجيدين الدفاع عنه، كما هي عادة الهولنديين.

ديزيريه: أنا لا أريد أن أدافع عنه، ولكن. نعم

عدنان: لا، لا، ولكن مفهوم تمامًا. لاحظي أننا نتكلم عن أسماء كبيرة في الواقع، وقيمتها المعرفية. لاحظي أنها قيمة عليا، حتى ونحن نتكلم عن بعض أدوار، (مشبوهة). ولكن العمق المعرفي لا جدال فيه.

واقع دراسة اللغة العربية في الجامعة الهولندية

عدنان: هل تعتقدين أن الجامعة الهولندية ما زالت إلى اليوم حريصة على هذا العمق؟ لأن هناك من يقول إن واقع دراسة اللغة العربية والعلوم الإسلامية المعاصرة في الجامعة الهولندية والفلمينية، ربما لم تعد بذلك العمق، ما رأيك؟

ديزيريه: سؤال صعب نوعًا ما، لأن هناك بالطبع، مثلما ذكرت، تم تحديد دراسة اللغة العربية والعلوم الإسلامية بسبب انخفاض الميزانيات. فقد لا تُدَرس اللغة العربية أصلاً بعد ربما سنة أو سنتين، وهذا طبعًا يؤثر على قيمة الدراسة. ولكن في نفس الوقت، هناك معاهد ومؤسسات تحاول أن تحافظ على هذا التراث الغني. فأتمنى أن يستمر هذا، أو تستمر الدراسات العميقة الفيلولوجية خصوصًا. وأتمنى أيضًا، على سبيل المثال، التنوع الثقافي في هولندا، وأيضًا في بلجيكا، وأن تُغني الدراسات العربية والعلوم الإسلامية، لأننا نلاحظ أن المستشرقين الحاليين ليسوا فقط هولنديين. على سبيل المثال، هم أيضًا من الجاليات العربية، يأتون إلى هولندا وبلجيكا بمعرفتهم، ويُسهمون في تطوير هذه الدراسات. وأعتقد أن هذا شيء مهم جدًا ومميز جدًا.

عدنان: إذن، أنتِ تعتبرين أن الدياسبورا العربية الإسلامية التي التحقت بالجامعات هناك، يمكن إدراجها ضمن هذا الإطار الاستشراقي؟

ديزيريه: صعب. طبعًا مفهوم الاستشراق أو المستشرق تحوّل عبر السنين. ولكن ما أريد أن أقوله: إن هناك علماء من الجاليات العربية أو من البلدان العربية، أتوا إلى هولندا وبلجيكا ورفعوا من دراسات اللغة العربية والعلوم الإسلامية.

عدنان: رفعوا من سويّتها، وربما ساهموا في خلق وضع جديد متحرك.

ديزيريه: نعم، أعتقد ذلك. وأيضًا، مثلًا إذا نظرنا، ما هو الفرق بين الاستشراق في القرن السابع عشر والآن؟ ممكن أن نقول أيضًا: إن المواضيع التي كان يدرسها المستشرقون المبكرون، كان الشرق، مثلا، شيئًا بعيدًا، واللغة العربية كانت شيئًا بعيدًا. ولكن الآن أصبح جزءًا لا يتجزأ من مجتمعاتنا، فبطبيعة الحال أيضًا، هذا أثر على دراسات هذه المواضيع.

عدنان: إذن، في الأنثروبولوجيا نتحدث عن أنثروبولوجيا البعيد وأنثروبولوجيا القريب. فيمكن الآن أن نتكلم عن الاستشراق البعيد والاستشراق القريب.

ديزيريه: ممكن.

عدنان: ويمكن حتى أن نسحب الآن لافتة الاستشراق لكي نتحدث في الواقع عن درس أكثر تعقيدًا. أرجو أن الجامعات الهولندية والبلجيكية أن تساهم فيه بذات الروح القديمة التي رسختها لايدن، والتي بها تحضرين معنا اليوم. ومن المهم الإشارة إلى هذه الديسباورا العربية الإسلامية، وكيف أنها التحقت بالجامعات، مثلًا، الهولندية والبلجيكية وصار لها إسهام وتفاعل داخل هذه الجامعات. ولكن، لا أعتقد أنها المورد الوحيد للدرس الاستشراقي الحديث إذا شئنا، لأنني أعتقد أن هذه الأسماء الكبرى التي كنا نتحدث عنها الآن أكيد أنّ لها أبناء وحفدة يحملون المشعل من داخل الهولنديين والبلجيكيين أنفسهم؟

ديزيريه: نعم، صحيح. الجاليات العربية الإسلامية وغير الإسلامية طبعًا. ولكن، أنا سعيدة جدًا عندما أنظر حولي كشابة هولندية، وأجد في زملائي ليس فقط الذين تخرجوا من دراسات عربية، ولكن بشكل عام، أجد أن هناك فضولًا لمعرفة الثقافات المختلفة. وهذا شيء يلهمني جدًا. وهذا أيضًا سبب من الأسباب التي جعلتني أؤسس مؤسسة إيوانا للتفاهم الثقافي.

ما يلهمني هو أن هناك الكثير من الشباب الهولنديين والبلجيكيين الذين يدرسون اللغة العربية، ليس بالضرورة في الجامعة، ولكن بشكل عام و يهتمون بالأدب العربي على سبيل المثال. هناك كثير من الأنشطة حول الأدب العربي في مدن مثل أمستردام أو لاهاي أو بروكسل. وهناك اهتمام فعلاً متبادل. فهذا شيء بالنسبة لي جميل جدًا. ولا أريد أن نقول: إن كل هؤلاء الأشخاص مستشرقون جدد، وربما كلمة “مستشرق” أو “مستشرقة” غير مناسبة في هذا الإطار، ولكن، هناك أشخاص مهتمون بمعرفة وزيادة المعرفة. وهذا جميل.

عدنان: وما يعنينا نحن هو تحديدًا هذا الفضول المعرفي والحوار الثقافي والأدبي، حتى ولو كان الاستشراق إطارًا لهذا الحوار. فما يعنينا هو الجوهر. شكرًا لأنك حملتِنا إلى هذا الجوهر ونقلتِ لنا روحًا هولندية معرفية لها صرامتها ولها عطاؤها المتجدد. ديزيريه كوسترس، شكرًا على حضورك بيننا.

ديزيريه: شكرًا جزيلًا على الدعوة. كان حوارًا جميلًا جدًا. شكرًا.

عدنان: بوجودك. أعزائي عزيزاتي، إلى اللقاء.

The Dutch School of Orientalism

I was invited for the podcast (On Orientalism) by the platform (Mujtama), with host Yassin Adnan, where I talked about Dutch Orientalism from the 16th century all the way to the present day. I found myself talking about old manuscripts and philologists in Dutch universities, as well as the many ways the Netherlands has looked Eastward over the centuries. It was a great way to reflect on multiculturality, intercultural contact, as well as the history of the Netherlands and the broader Orient

Here you can read the English translation as I have translated it

Adnan: Dear listeners, welcome. The Dutch school is considered one of the most important schools of classical Orientalism and played a pioneering role in the field of Arabic studies since the 17th century, especially after the establishment of the University of Leiden in 1575 AD, and the establishment of the Chair of Arabic Language in 1613, in addition to the establishment of an Arabic printing press there early in 1683

However, Dutch Orientalism has suffered from neglect by Arab researchers, and the studies written about it in Arabic so far are rare and limited. For this reason, today we will try to shed some light on the Dutch Orientalist school. We have invited to this meeting the Dutch researcher and academic Desiree Custers, a graduate of the Catholic University of Leuven in the field of Arabic and Islamic studies, and director of the EWANA Center for Cultural Understanding. Desiree, welcome

Desiree: Hello, thank you very much for the invitation. I am very happy to be here with you

Adnan: So are we. I would like to start with a paradox: the presence of the Arabic language in the Netherlands was perhaps earlier than the presence of Dutch itself. Thomas Erpenuis, the first professor of Arabic in Leiden, gave an inaugural speech on the superiority and high status of the Arabic language on May 14, 1613, almost two centuries before there was a Dutch language. The Dutch language did not appear until the end of the eighteenth century. What do you think of this paradox

Desiree: Thank you again for the invitation and welcome all the listeners. Of course, the Dutch language was present in the Netherlands, but it was not an academic language or an elite language, let’s say. Dutch was widespread but not yet standardized. And indeed, Thomas Erpenius stressed the importance of Arabic. To note, he was not the first professor of Arabic in the Netherlands, but he was the first to hold the chair, as you mentioned, in 1613

Dutch became a standardized language in the Netherlands during the Protestant Reformation, and also when Dutch was linked to the development of Dutch nationalism in the context of the war with Spain, e.g. the Dutch War of Independence. Arabic was considered important for a theological purpose, which we will talk about more later, and also because of the beginning of relations between the Dutch Republic and the countries of the East or the Arab countries

Erpenius

Adnan: Looking at these Arab countries, we can start with Morocco. Even as we talk about Erpenius, let’s not forget Al-Hajari, the Moroccan ambassador

Desiree: Right. I mean, one can also wonder how a person like Erpenius, who lived in the late 16th century, learned Arabic at all, because there wasn’t much material to study Arabic. Erpenius, before becoming a professor of Arabic, traveled to several European countries, including France, where he met a Moroccan person named Ahmed ben Qasim al-Hajari, who was a Morisco (a Muslim who was forcibly converted to Christianity in Andalusia). He was there as an envoy from Morocco. They developed a friendship, and later when Erpenius returned to Holland and became a professor, he received a letter from al-Hajari saying that he would visit Holland. Thanks to this friendship, al-Hajari remained Erpenius’ guest in Holland throughout the summer of 1613. Indeed, he helped Erpenius develop his dictionary, and they also held discussions about religion and various topics

Erpenius, Grammatica Arabica, 1617: source / إربينيوس، قواعد اللغة العربية، 1617: المصدر

Adnan: And this was also the aspect that you were kind enough to point out, that there was of course Dutch nationalism versus the Spanish. The Dutch as Protestants versus the Catholics in Spain. Is this perhaps what led the Dutch at some point towards the Moroccans, considering that Spain was a common enemy for both of them

Desiree: Yes, let’s start from the beginning. We can say that Dutch Orientalism began in the late 16th century, and this was a period when the Dutch were in a war of independence with Catholic Spain, which occupied the Netherlands. So there was a war of independence, and in this war the Protestant dimension was important for what would become the Dutch Republic, because that was something that distinguished the Netherlands from Spain. So, the first Orientalists were theologians, and many saw Islam as better than Catholicism

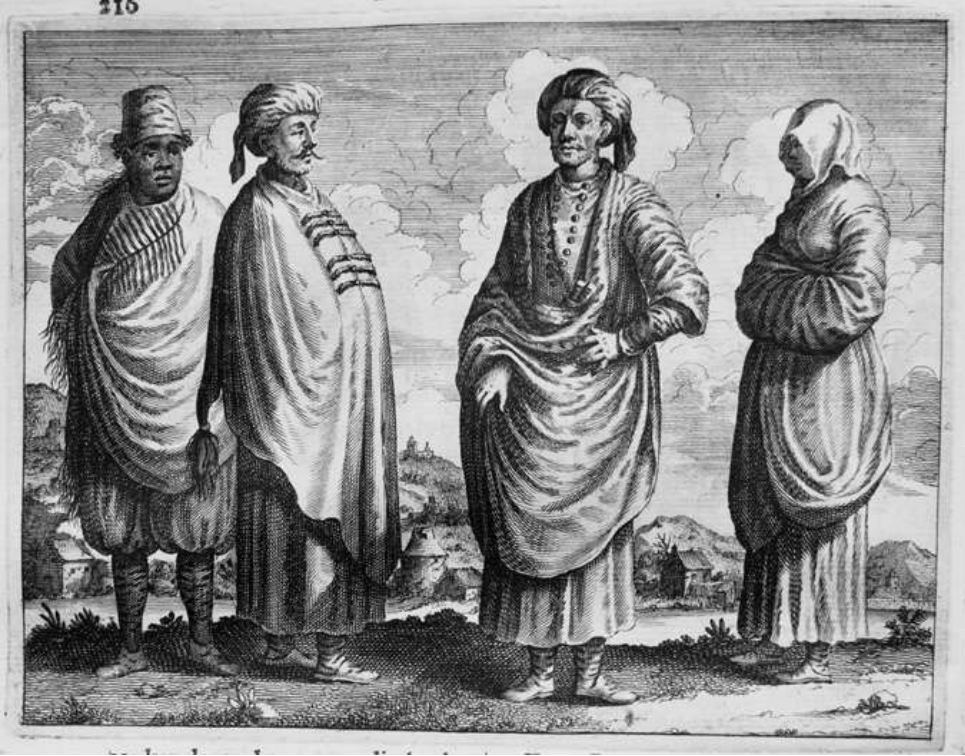

The Dutch Republic followed a policy of “the enemy of my enemy is my friend”, the enemy of Spain being at the time Morocco and the Ottoman Empire, and so they developed relations with them. By the way, the period of the war of independence, which lasted for 80-years, also coincided roughly with the Golden Age of the Dutch Republic, when the Dutch Republic developed a lot of relations with the East / Orient. Morocco was the first country with which the Netherlands had a trade treaty, in 1609

“Ambassadors from Salé.” Engraving from Olfert Dapper, Naukeurige beschrijvinge der Afrikaensche gewesten… (Amsterdam, 1676). Courtesy of Special Collections of the University of Amsterdam, otm: OM 63–360: source / “سفراء من سلا.” نقش من أولفيرت دابر، Naukeurigeomschrijvinge der Afrikaensche gewesten (أمستردام، 1676). بإذن من المجموعات الخاصة بجامعة أمستردام: المصدر ، OM: OM 63–360

Franciscus Raphelengius

Adnan: You are referring to the theological depth now. I also think that even in the case of the Arabic language, in a sense, theology has been dominant. And there are those who say: what happened with the Arabic language in the Netherlands is not very different from what happened in Germany. It was not initially studied for its own sake, but rather for its strong vocabulary and precise grammar, in order to provide a better understanding of the Old Testament. Because the language of the Old Testament, Biblical Hebrew, was considered among the extinct languages. Was it thus a coincidence that the first professor of Arabic at Leiden University was Franciscus Ravelingius, the same professor who also taught Hebrew

Adnan: I made a mistake in the name, right

Desiree: Well, because Latin was an academic language in that period. He has two names, “van Ravelingen”, the Dutch name, and “Raphelengius”, such as “Van Erpen” and “Erpenius”. van Ravelingen was the first professor of Arabic and Hebrew, but he was not the first to hold the chair for Arabic Studies

Indeed there was a close relationship between Hebrew and Arabic, as you mentioned. The Hebrew language was a dead language, so there was not enough lexical knowledge to rely on it to understand the Old Testament or the Bible, so they used Arabic and termed Arabic the daughter of Hebrew

Adnan: Yes, and others called the Arabic language the maid of theology

Desiree: The maid of theology, because of her proximity to the Hebrew language. Indeed, interest in Arabic was initially of theological nature, in order to use it to increase the understanding of the Bible. Of course, this was in the context of Protestant reform, a movement that called for the re-reading of texts. Therefore, there was a new interest in reading it and also in understanding it. This through using semitic languages more generally, such as Arabic, Aramaic and Syriac, and of course also in the framework of the “Humanist” movement that had its center in Leiden in the Netherlands

Adnan: Indeed, there is this Protestant Reformist aspect, and there is also the aspect, sort to say, of “enlightenment”, because the winds of enlightenment began to blow in Europe at the time. Here, I can mention Adriaan Reland, although we should also not forget Van Ravelingen. What role did Adriaan Reland play in the midst of the transformations that the Orientalist approach has known in the context of the Enlightenment movement

Desiree: In the context of the enlightenment, interest in the East increased from initially being an interest in Arabic for theological goals, to later being also to understand Islam and understand Arabic for trade purposes with the East. Also due to the manuscripts, Dutch Orientalists noticed that there was a lot of science in Arabic manuscripts, so there was an interest in literature and culture, etc

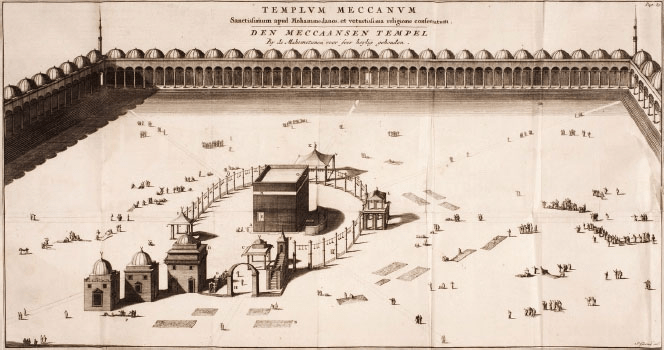

Adriaan Reland was one of the first early orientalists in the Netherlands, he lived in the end of the 17th century, and was a professor of Arabic in Utrecht. He wrote one of the most important books influencing the Dutch’s vision of Islam. The strange thing is that he did not travel even once, he never left the Netherlands. All of his information was based on preliminary sources. His most important book, published in 1717, was titled: “De Religione Mohammedica”. In it, he used the Arabic language to understand the Islamic religion and doctrines. This book was important for several reasons: first, he called for a return to primary sources to understand the Islamic religion, and secondly, he insisted on the importance of teaching the Arabic language to understand Islam

“De Religione Mohammedica” is divided into two parts: the first part is a translation of an Islamic doctrine into the Latin language accompanied by notes explaining to the Dutch reader on the Islamic religion. In the second part, Reland refuted 38 wrong ideas about Islam that were widespread at the time in the Dutch Republic by using Arabic-language primary sources

The first reliable image in the form of an engraving of the holy mosque in Mecca in the second edition of De religione Mohammedica (1717) source / أول صورة موثوقة على شكل نقش للمسجد الحرام في مكة المكرمة في الطبعة الثانية من كتاب عن الدين المحمدي (1717) المصدر

Adnan: Can we say that this was, in a sense, seen as against the Spanish Catholics

Desiree: We could

Adnan: Because most of these ideas developed in a Catholic environment, especially after the Muslims were expelled from Andalusia

Desiree: His book was even banned by the Pope in Rome, and he was accused of Turkish Calvinism, a term some Catholics used at the time to accuse Protestants of being so close to the Turks that they were doing propaganda for the Ottomans. But I think he really tried to be objective in his research

The shift in the role of the Arabic language for the Dutch

Adnan: Speaking of the interest in the Arabic language, we know that Dutch society in general is not keen on spending public money on things deemed useless. I mean, the Dutch are known for this characteristic, and when they spent resources on the Arabic language, they always justified their spending, at first by saying that the Arabic language is a “servant of theology.” But later, as you kindly pointed out, there was the relationship with the Ottomans, and then later, when the Dutch arrived in the Muslim Southeast Asia region in the late sixteenth century, they discovered that the Arabic language was useful in the relationship with these Islamic societies. I want to ask you about the different roles the Arabic language played for Dutch society in general, and for Orientalists specifically. How do you see this

Desiree: Thank you for the question. I think that Orientalism in the Netherlands was different from its neighbors, because first of all they did not have any colonies in the Arab countries, as opposed to for example France. And they did not have any missionary trips in the Arab countries. So the role of language was different from its neighbors. As we mentioned at the beginning, the interest was initially for theological reasons, and later for trade and gaining knowledge from Arabic manuscripts

As for the colonial period, Arabic was a source or a means of understanding Islamic texts written in Arabic, which were used in Indonesia, for example. So the language was not a means of communicating with the Indonesians, but more for understanding the religious texts. Later, of course, after Indonesian independence, we can say that the interest in teaching Arabic decreased a little

And recently, especially after Edward Said’s criticism, teaching has become more about dialects in Dutch universities than classical Arabic. Classical Arabic was important for philological studies, but after Edward Said’s criticism, the study shifted from Orientalism, to the study of Arabic and Islamic sciences, and they also study dialects. But I think now there is a kind of decreased interest in teaching Arabic at universities. Two weeks ago, we saw in the Dutch news that Leiden and Utrecht University might cancel Arabic studies because there is not enough budget

Nevertheless, we can ask ourselves if the university is the best place to teach Arabic, because Arabic has become an integral part of Dutch society now. There are Arab communities that speak Arabic, and there are second and third generations of Moroccans, for example, who have learned Dutch and are interested in learning Arabic. But not everyone goes to university in the Netherlands, this is only a small part of Dutch society. So, Arabic is also taught in schools outside the university framework, and I think this is an important development that we can discuss further

Adnan: Exactly. I mean, the university is no longer the only place to teach the language, as you mentioned. There is a shift from the initial interest in classical Arabic with its philological depth and content and so on, to paying attention to dialects, especially the dialects of communities that settled in the Netherlands. I am thinking of the Moroccan community, for example

But don’t you feel, Desiree, that after the events of September 11, this interest in the Arabic language is no longer an interest in the language itself, but has returned to be linked again to Islam? Arabic was linked to Islam within the framework of, for example, the interest in radical Islam that began to spread in Europe and across the world. Arabic studies or chairs were merged with Islamic studies in more than one Dutch university. What do you think of this as a project to “Islamize” Arabic knowledge in Dutch universities? And doesn’t this mean that the Arabic language has once again returned to play its old role as a “servant” of theology

Desiree: Good question. I think we can start by saying that the study of Orientalism in the Netherlands has always known two currents: the philological current, which is still present, and the politicized current. These two have existed side by side, I think we can say that, and there are examples of that. As for what happened after 9/11, it is true that the study of Arabic was linked to more political topics, and this was even before 9/11, when there was criticism directed at the Arab communities in the Netherlands. For example, the most important politician criticising multicultural society was Pim Fortuyn. This was before 9/11. And after 9/11, there was the murder of Theo van Gogh, a famous Dutch media personality

This had a huge impact on Dutch society and on the discussion about the integration of the Arab and / or Islamic community in the Netherlands. So of course, after this incident, there was a kind of politicization of Orientalism or the politicization of the study of Arabic and Islamic studies. In other words, the focus became on radical Islam in the Netherlands or the possibility of integration. Arabic was essential in this context because orientalists had to read Islamic texts and look at these texts to determine how compatible they were with Dutch society. This was one of the main questions asked at the time. Secondly, Arabic was essential for communication with the Arabic-speaking communities in the Netherlands. It was a sort of “servant language”, but for another purpose of course

The influence of the thousand and one nights

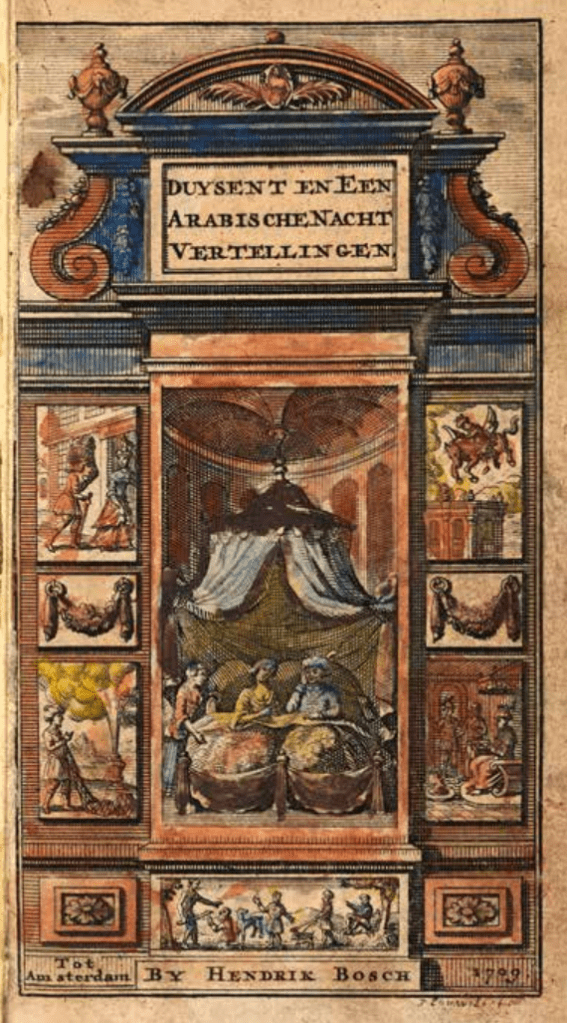

Adnan: Let’s return to one of the texts that the early Orientalists paid attention to, and that constituted an inspiring material, not only for Orientalists and their readers, but even for politicians. I am thinking of Antoine Galland’s French translation of The Thousand and One Nights. I do not know where I read that the Dutch translation may have been published before Antoine Galland’s translation, but as we can see, the French translation of The Thousand and One Nights had a great influence in France and across Europe and across the world. While we feel that the Dutch translation did not have the same influence. Do you have an explanation for that

Desiree: Yes, about the Dutch translation being before the French, I did not find this information. But the first translation, or better yet the first part translated by Galland, was in 1704. And I know that in the Dutch Republic there was a pirated French version of this book, which appeared a year after this translation

Adnan: It appeared in French

Desiree: In French, but as a pirated copy. It was available to the Dutch elite, because, as we mentioned, Dutch wasn’t widely spoken at the time. But everyone was reading, especially the elite. They read The Arabian Nights, but the book didn’t receive the same enthusiasm as it did in France. It didn’t have the same impact

De duizent en eene nacht, Arabische vertellingen, Amsterdam, Aldewerelt 1738, hand-coloured frontispiece by Jan Lamsvelt after David Coster Source: Universiteit van Amsterdam / ألف ليلة وليلة، حكايات عربية، أمستردام، ألدويريلت ١٧٣٨، صفحة الغلاف الأمامية ملونة يدويًا من تصميم يان لامسفيلت، عن ديفيد كوستر. مصدر: جامعة أمستردام

Adnan: Can we explain the lack of influence through the difference in mentality? The Dutch mentality, which differs from the French or British mentality, for example

Desiree: Yes, that’s one interpretation: that the Dutch Calvinist mentality was less inclined toward tales of anecdote or humor, such as the One Thousand and One Nights. They were more inclined toward tales of wisdom, such as the tale of Hayy ibn Yaqzan

Adnan: Ibn Tufayl

Desiree: Yes, Ibn Tufayl

Adnan: Ibn Tufayl entered Dutch literature

Desiree: Yes, Hayy ibn Yaqzan was translated three times. The first time was in 1672, and then again in 1710. In this last version, Adriaan Reland, whom we mentioned, added footnotes explaining the events of Hayy ibn Yaqzan to the Dutch reader

Adnan: And Ibn Tufayl’s philosophy as well, because it’s a philosophical vision

Desiree: Part of the Calvinist mindset is that they were more interested in the dialectical dimension than the mystical dimension in Ibn Tufayl’s book. However, One Thousand and One Nights inspired several Dutch writers to write what we call Oriental tales. One of the most famous of these writers is Jan Nomsz, who wrote plays in the same vein as One Thousand and One Nights

Adnan: Strange, then. Nevertheless, there is an influence. So, let’s respect the seriousness of the Dutch mentality and go directly to the university. Leiden University, where Oriental studies began in 1591, and its affiliated Dutch Near East Institute, which was founded in 1939. I want to ask you about Oriental studies at Leiden University. Do you approach this field as a purely academic field, or perhaps as a sociopolitical phenomenon

Desiree: I think the trajectory of Leiden University, and particularly the teaching of Orientalism there, has always been influenced by the social or political context. Even the beginning of Leiden University—the story, of course, is that it was founded as a gift from Willem van Oranje to the city of Leiden because of the city’s resistance against the Spanish. So from the beginning the university was established in a certain socio-political context. Later, we can also see, for example, that many early Orientalists played a role in translating commercial letters for the India Company

Adnan: The Chinese company

Desiree: Chinese, yes. And during the colonial period, there was a close connection between the university and Indonesia, such as courses on Indonesia, or courses on Islam in Indonesia. A prominent figure who contributed to this was Christiaan Snouck Hurgronje. And as we mentioned after 9/11, many scholars at Leiden studied radical Islam and other contextual topics

But at the same time, there is always a philological tradition at Leiden University, and the institute you mentioned is an example of this. There are institutes that study manuscripts at Leiden University. Incidentally, I would like to mention that Leiden University, of all the universities in the Netherlands, has had a major role in defining or shaping the study of Orientalism, not only in the Netherlands, but in Europe in general. I think this has three reasons. First, the influence of Orientalists who worked at Leiden University, starting with Erpenius and going on to Golius, or other figures like Reinhart Dozy, and Juynboll. All of this led to Leiden University’s approach to rigorous textual analysis. So I believe this first. Second: The manuscripts at Leiden University. No university in the world, or at least in Europe, has this quantity of manuscripts

Adnan: I visited there and enjoyed spending a whole day among the Arabic manuscripts there

Desiree: That’s great! There are two main collections. The first is from Jacob Golius, who was Erpenius’ successor. He collected manuscripts in Morocco with the help of Al-Hajari, whom we mentioned earlier, and also in Constantinople and Aleppo. He collected more than, I think, 400 manuscripts. But the largest collection came from a man named Levinus Warner, who was an envoy for the Dutch to Constantinople and lived there for a long time. With the help of his network, his hobby was to collect manuscripts, and he collected more than a thousand manuscripts. This is quite remarkable, and he donated the manuscripts to the University of Leiden after his death. Here, for example, we find “The Ring of the Dove” by Ibn Hazm, the only copy of which is at Leiden University. Also, for example, one of the volumes of Al-Tabari is in Leiden. This is something to be proud of, and now they are working on digitizing all of these manuscripts

Brill Publishing House

Adnan: When we talk about manuscripts, we’re also talking about the printing of Arabic books. Here, we must mention the Brill Publishing House in Leiden, the venerable Dutch publishing house founded in 1683, which is exceptional by all standards. Before the printing press was introduced to the Arab world, Brill began receiving Arabic manuscripts immediately after they were able to print in the Arabic script. Suffice it to say that Brill printed the Encyclopedia of Islam and the heritage atlases of the Arab and Muslim countries. We cannot speak of Leiden University here without mentioning Brill Publishing House

Desiree: Yes, the Brill publishing house played a major role in printing books for Dutch Orientalists, starting with Erpenius, and of course later on, many Orientalists had their works printed there, because they were very professional in printing manuscripts or non-Western scripts

Adnan: Latin

Desiree: Yes, Latin, as well as Arabic, Sanskrit, Hebrew, and other languages. The two most important projects I would like to mention are: First, the History of al-Tabari, which was a major achievement for Brill. One of the manuscripts of the History of al-Tabari was at Leiden University, and it was the orientalist de Goeje who took on the project to have the complete History of al-Tabari published by Brill. He worked with orientalists from different countries around the world to collect all the volumes—I think there were twenty in total—to make a complete book. So that was one of Brill’s major projects, and of course the encyclopedia

Adnan: The famous encyclopedia

Desiree: The famous one, yes. Brill began publishing this encyclopedia in the late nineteenth century, and of course it was a huge effort… An encyclopedia of this size required major collaboration. European orientalists contributed to the first edition. Later, there was criticism from the Arab world that no Arab or Muslim specialists contributed to the encyclopedia. They tried to change this in the second edition, and are currently working on the third edition

Adnan: Let’s not forget that when we talk about the beginning of the printing press in 1683, there was no printing press in the Arab world. It was the first Arab printing press, a pioneer not only in the Arab world, but also worldwide. That’s why we emphasize its importance, even for us, and not just for the Netherlands or Leiden University

Desiree: Yes, yes. And they are still working, still printing books, and working virtually. On their website you can find lots of magazines and books. Until 2006 they had a bookshop in Leiden’s city center where they sold books, but unfortunately it closed

Adnan: Like many specialized scientific libraries

Desiree: This can, of course, be explained by the fact that philological studies have lost importance in the field of Oriental studies

Adnan: Exactly, it’s really a loss. However, the library is still available. I can tell you that two days ago, I received via email the program of a symposium in Italy, a symposium that includes a group of people interested in Arab and Islamic culture. There is a major symposium on culture and literature in Morocco in Italy, and in the message I received, they indicate that the symposium proceedings will be published by the Brill Press

Desiree: That’s great

The Juynboll family

Adnan: Since it’s a digital edition, it’s still being published, both virtually and electronically, at least. There’s another landmark of Dutch Orientalism. Besides the university and the printing press, there’s the Junpoel family. This family is considered the most famous Orientalist family, not only in the Netherlands, but perhaps in all of Europe. How do you, Desiree, trace the Orientalist trajectory of this family, which began during the first half of the nineteenth century and ended with the death of Gautier Juynboll in 2010

Desiree: Yes, this family played an important role in establishing Orientalist studies in the Netherlands. The first of the four generations was Theodoor Juynboll, who was truly a specialist in Islamic law and who founded this study and contributed significantly to the methodology of Islamic law studies in the Netherlands

His son, Abraham, taught at the Dutch Civil Service Institute for Indonesia, where, among other subjects, he taught the Javanese language. We can say that interests changed from the first to the second generation, Abraham was involved in the goals of the Dutch state. And concerning Abraham’s son, now we move on to

Adnan: The third generation

Desiree: Representing the third generation, Theodore (same name as his grandfather) wrote a very important book for the education of Dutch officials in Indonesia, a book titled “Handleiding tot de kennis van de Mohammedaansche Wet”. At the time, they called it “Muhammadan Law,” in 1903. This book remained the reference for officials in Indonesia for decades

Adnan: Dutch employees working in Indonesia during the Dutch colonial period of Indonesia

Desiree: Yes, that’s true. Of course, after Indonesia’s independence, in general, Dutch interest in Oriental studies declined, because there was no prospect of work in Indonesia. Consequently, there was less interest in studying Orientalism. Here, we find that there was more room for philological topics again

The last of the Juynboll generation, Gautier, was an Orientalist philologist par excellence, meaning he specialized in Hadith, and he was very passionate about this subject. He wrote the famous book the “Encyclopedia of Canonical Hadith”, published in 2007. I heard from his colleagues at Leiden University that every morning he would go to the Oriental Books Library in Leiden and study Hadiths and their isnads. He was very passionate about this subject. He would spend long hours studying the subject

Adnan: But his breath was cut short in 2010 with Gauthier’s death and passing. Fortunately, the entire family heritage was not lost, because the archives and manuscripts were all donated to Leiden University. I reviewed some of these archives there. Then there is the foundation, the Juynboll Stichting, which today aims to promote the study of the Arabic language and Islam. Do you believe that this foundation represents, in a sense, an extension of the contributions of these four generations

Desiree: Yes, absolutely, because the foundation supports researchers from all over the world to continue their philological studies at Leiden University. I think that’s very important

Muhammad b. Ya’ub al-Khuttuli: Horse anatomy, 1343. It was acquired by Warner and is part of the collection of the University of Leiden: source / محمد ب. يعقوب الختولي: تشريح الخيل، 1343 وقد حصل عليه وارنر وهو جزء من مجموعة جامعة لايدن: المصدر

Reinhart Dozy

Adnan: Exactly. So we cannot end our conversation without mentioning another landmark of Dutch Orientalism? I’m thinking of Reinhart Dozy, the pioneer of Andalusian studies, who was neither Arab nor Spanish, yet authored the most important reference book on the history of Muslims in Spain. What is the significance of an Orientalist from outside the Arab-Spanish orbit, and a Dutch in particular, tackling this history

Desiree: Yes, thank you for the wonderful question. Of course, his book about Muslims in Andalusia, in Spain, was one of the most important books on the subject. I’m sure you mentioned the book in more than one episode of this program. I think it was important that he first of all came from outside the Spanish and outside the Arab framework, as he could thus look at the history of Muslims in Spain in a more neutral way. This is because he did not follow the Arab narratives that say: Andalusia was the ideal period, nor does it follow the Spanish narratives that

Adnan: That the Muslims’ stay in Andalusia was a catastrophe, a disaster, and a calamity that affected them and their history

Desiree: Yes, and focus on the “Reconquista” more than anything else. And I think he was able to look at the subject more impartially. Because as a Dutchman and as a researcher based in the Netherlands and associated with the University of Leiden, he had a lot of manuscript sources available to him. He researched new primary sources on the subject

Yet, of course, in the context of the war against Spain still being in the collective Dutch memory, he was skeptical of anything that found its source in Spain because of that history: the eighty years war of Dutch independence. But at the same time, we can say that he wasn’t just a Dutch Orientalist, because he wrote in French, and he was influenced by the ideas of Renan and Gobineau. He was also looking at Andalusia in a specific context, influenced by existing ideas that gave great importance, for example, to race in his research

Adnan: By the way, I’ve actually mentioned Dozy in more than one previous episode. I always mention him to praise his scholarly rigor, because the researcher emphasized that there was no way to complete a scientific historical account of Andalusia’s history without verifying the most important texts related to this history. For this reason, he verified “Al-Bayan” by Ibn Idhari al-Marrakushi, “Al-Mu’jab fi Talkhis Akhbar al-Maghrib” by Abd al-Wahid al-Marrakushi, “Nuzhat al-Mushtaq” by al-Sharif al-Idrisi, and he has also begun verifying “Nafhat al-Tayyib” by al-Maqqari. The rigor and patience of its author can only be either German or Dutch

Desiree: It could be, but I think it is a rigour more specific to Dozi than anything else

Adnan: You attribute it to the person, not the country

Desiree: Because even before he wrote this book, and this book took twenty years to write, he was very meticulous in his research on manuscripts at Leiden University when he was still a student. He wrote this dictionary on Arab clothing because of his studies of manuscripts, and he was really unique in his patience. And I read that even when he got married in 1844, he and his wife spent their honeymoon in Germany, even during their honeymoon he was searching for manuscripts. I don’t know what his wife thought of it, but on this trip, he found a manuscript and an important source in the German city of Gotha on the history of Andalusia, which influenced his writings

Adnan: Amazing! As I speak, we owe him his research, in fact, and the books he edited, which enabled him to truly reconstruct the vision of Andalusian history and give it a positive presence in constructing this history for the Arab narrative. Hence, he was a very fair man in constructing that history and his writings

Christian Snouck Hurgronje

Adnan: There is another character that I would like to mention, Christian Snouck Hurgronje, who is considered by many a genius. But at the same time, others criticised him for his role during the Dutch colonial period, to the point that he was directly accused of espionage. I don’t know to what extent you agree with this accusation

Desiree: The character of Snouck Hurgronje is one of the most famous and controversial of Dutch orientalists. Not only because of his role in contributing to the development of colonial policy in Indonesia, but also because of his journey to

Adnan: The Hajj

Desiree: The Hajj. Because of this journey he was accused of espionage. But I think the word “spy” may be too strong for him, because he was an anthropological researcher more than anything else. And that’s what he did in Mecca. I mean, he went there on behalf of the Dutch government to write about the Indonesian community during the Hajj. And if the Indonesian community has Islamic nationalist ideas

Adnan: No, after all, when Snouck returned from Hajj, he wrote reports and told the Dutch administration: Try to harass the Indonesians so they don’t go to Hajj. Perhaps because he felt they were being religiously motivated, and this was probably against the interests of the Dutch administration

Desiree: Well, thanks for asking. Of course, the way he conducted his research these days, at the present time, would not be acceptable. It is clear that his method of conducting the research is questionable. However, we cannot say 100% that he made the journey in disguise, because he was, according to himself, a Muslim. He had the right to perform the Hajj. Of course, whether he was actually a Muslim or not, only he knows. We cannot judge his intentions, and he was also under pressure from the Dutch context not to be a Muslim, and pressure from various other parties. But he wrote in letters to his friends early on that he had converted to Islam

Adnan: He converted to Islam. He married an Indonesian woman and had four children with her

Desiree: Whether he was on the trip in disguise or not is a question. As for his study of Indonesians during

Adnan: The Hajj

Desiree: During the Hajj. The Dutch government commissioned him to do this research. This research led to the first complete book about life in Mecca for a Dutch audience. It was the first book that allowed the Dutch to understand the way of life in Mecca. It also had a positive impact on the image of Muslims and the Hajj. It also had a positive impact, in a way, against stereotypes. The topic is thus not so black and white

Adnan: Not at all, it’s not black and white. We’re actually here to study these aspects in their intersection. Of course. It’s natural for scientific matters to overlap with multiple, sometimes conflicting, interests

Desiree: I want to mention something else. Snouck Hurgronje was the first person to photograph Mecca, and daily life in Mecca, especially with a focus on Indonesians. He even recorded the call to prayer in Mecca. He was one of the first anthropologists to research, not just write, but also photograph and record. When you see the photos now, you see that he did something beautiful as well

Sound fragment from the Hijaz made on wax cylinders in 1909, commissioned by Snouck. The Adhan / مقطع صوتي من الحجاز، أُنتج على أسطوانات شمعية عام ١٩٠٩، بتكليف من سنوك. الأذان

Adnan: Exactly, amazing and important knowledge

Desiree: The topic is kind of

Adnan: Exactly, very complicated. I envy him because he has a high-profile lawyer: you’re adept at defending him, as the Dutch usually do

Desiree: I don’t want to defend him, but… yes

Adnan: No, no, but it’s completely understandable. Note that we’re talking about big names in reality, and their scientific value. Note that it’s of high value, even as we’re talking about some (suspicious) roles. But the scientific depth is indisputable

The reality of studying Arabic at Dutch universities

Adnan: Do you believe that Dutch universities still maintain this depth? Some argue that the study of Arabic and contemporary Islamic studies at Dutch and Flemish universities may no longer be as profound. What do you think

Desiree: It’s a rather difficult question, because, of course, as I mentioned, the study of Arabic and Islamic studies has been limited due to declining budgets. Arabic may not be taught at all in a year or two, and this of course affects the value of the study. But at the same time, there are institutes and foundations trying to preserve this rich heritage. I hope this continues, or that in-depth philological studies in particular continue. I also hope, for example, that cultural diversity in the Netherlands, and also in Belgium, will enrich Arabic studies and Islamic studies, because we notice that current Orientalists are not only Dutch. For example, they are also those from Arab communities, coming to the Netherlands and Belgium with their knowledge and contributing to the development of these studies. I think this is something very important and very special

Adnan: So, do you consider that the Arab-Islamic diaspora that joined the universities there can be included within this Orientalist framework

Desiree: Difficult. Of course, the concept of Orientalism or the Orientalist has shifted over the years. But what I want to say is that there are scholars from Arab communities or Arab countries who came to the Netherlands and Belgium and advanced the study of the Arabic language and Islamic sciences

Adnan: They raised its level, and perhaps contributed to creating a new dynamic

Desiree: Yes, I think so. And also, for example, if we look at, what is the difference between Orientalism in the seventeenth century and now? We could also say that the topics that early Orientalists studied – the Orient -, for example, was something distant, and the Arabic language was something distant. But now it has become an integral part of our societies, so naturally, this has also influenced the study of these topics

Adnan: So, in anthropology, we talk about distant anthropology and near anthropology. Now, we can talk about distant Orientalism and near Orientalism

Desiree: Possibly

Adnan: We can remove the Orientalist banner now to talk about a more complex issue. I hope that Dutch and Belgian universities will contribute to it with the same ancient spirit that Leiden established, and with which you are present with us today. It is important to point out this Arab-Islamic diaspora, and how it joined, for example, Dutch and Belgian universities and contributed and interacted within these universities. However, I do not believe that it is the only source for the modern Orientalist lesson, because I believe that these great figures we were talking about now certainly have sons and grandsons who carry the torch from within the Dutch and Belgians themselves

Desiree: Yes, that’s true. The Arab Muslim and non-Muslim communities, of course. But, I’m very happy when I look around me as a young Dutch woman, and I find among my colleagues not only those who have graduated with Arabic studies, but in general, I find a curiosity to learn about different cultures. And this is something that inspires me a lot. And this is also one of the reasons why I founded the EWANA Center for Cultural Understanding

It inspires me that there are so many young Dutch and Belgians who study Arabic, not necessarily at university, but in general, and who are interested in Arabic literature, for example. There are a lot of activities around Arabic literature in cities like Amsterdam, The Hague, or Brussels. And there is a real mutual interest. This is something that I find very beautiful. I don’t want to say that all these people are new Orientalists, and perhaps the word “Orientalist” is not appropriate in this context. Rather, they are people interested in knowing and increasing knowledge. And this is beautiful

Adnan: What concerns us specifically is this intellectual curiosity and cultural and literary dialogue, even if Orientalism serves as a framework for this dialogue. What matters to us is this essence. Thank you for taking us to this essence and conveying to us a Dutch intellectual spirit that is both rigorous and constantly giving. Desiree Custers, thank you for being with us

Desiree: Thank you so much for the invitation. It was a very really nice conversation. Thanks

Adnan: With you. My dear listeners, goodbye

أضف تعليق