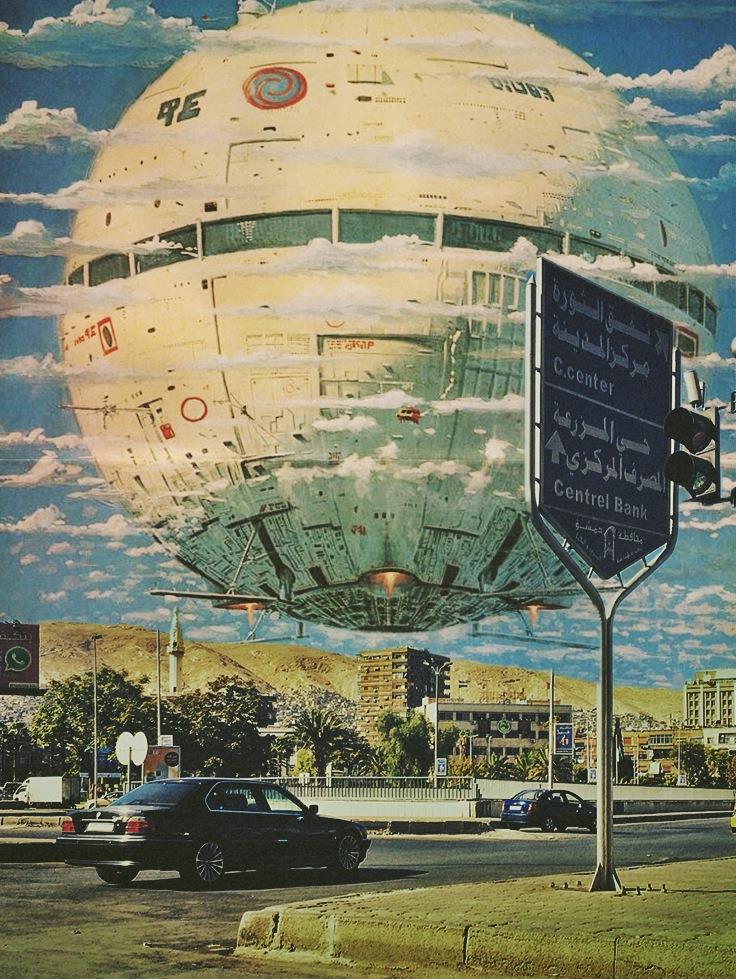

Picture by Syian artist Ayham Jabr, from the serie Damascus Under Siege-7. Source: SYRIA.ART

الصورة فوق للفنان السوري أيهم جبر من سلسلته دمشق تحت الحصار. مصدر

For English scroll down

الخيال العلمي العربي والإفريقي: إستعادة الماضي، تأمل في الحاضر، وتصور المستقبل

مقدمة

مع أنّ المعجبين بالخيال العلمي قد يعرفون عن أدب الخيال العلمي من المنطقتين العربية والإفريقية، فهو مازال فئة أدبية لم تحصل على الانتباه الذي تستحقه من قراء العالم. وهذا رغم أن إصدار الخيال العلمي العربي والإفريقي بدأ في بداية القرن الماضي

ومع أنّ العالم العربي والإفريقي كثيراً ما يوصف في العلوم السياسية والإجتماعية والأدبية بأنهما منطقتان مختلفتان، إلاّ أنهما متشابهتان، وهذا التشابة يظهر في الخيال العلمي. من خلال وجهة نظر عامة وواسعة، تُحاول هذه المقالة أن تُطهِر كيف يقوم الخيال العلمي العربي والإفريقي بثلاثة أهداف: تصور المستقبل، إستعادة الماضي، والتأمل في الحاضر

أدب الخيال العلمي

الخيال العلمي، بِرأيي، أحد الفئات الأدبية الأكثر فعالة لتشكيل أفكارنا وتصوراتنا عن المستقبل والتعبير عنها. غرابة قصص الخيال العلمي تتسبب بنوع من الإغتراب المعرفي لأنها وُضعت في عالم بديل أو غريب ولأنها تصف أحداثاً تتجاوز إطار التجربة الإنسانية العادية

يطرح الخيال العلمي أسئلة فلسفية حول معنى أن تكون إنساناً: من الناحية الفردية والإجتماعية والدينية، بالإضافة إلى علاقة الإنسان مع البيئة والتقنية. عبر العقود تبلورت أنواع مختلفة من الخيال العلمي، مثل الأفروفيوتورِسم (أو المستقبليّة-الإفريقية، وهوالحركة المستقبلية في الموسيقى والفنون المرتبطة اصلاً بالأفارقة الأمريكيين)، والخيال العلمي النسوي، والفيوتورِسم العربي (أو المستقبلية العربية، وهو حركة مستقبلية جديدة مرتبطة بالعالم العربي) والفيوتورِسم الإفريقي (حركة مستقبلية جديدة مرتبطة بالقارة الإفريقية). وترى هذه المقالة أن لفيوتورِسم العربي ولفيوتورِسم الإفريقي جزء من الخيال العلمي العربي والإفريقي

خيال علمي ذاتي للمنطقة العربية والإفريقية

كان الكاتب والناقد الثقافي الأمريكي، مارك ديري، الأول الذي طرح مفهوم الأفروفيوتورِسم، وهو حركة فنية تنظر في تقاطعات مواضيع الخيال العلمي، والسواد (بلاكس)، والعِرق، والتقنية والمستقبل، والحركة المرتبطة اصلاً بالأفارقة الأمريكيين . آنذاك، تساءل مارك ديري لماذا هناك القليل من الأفارقة الأمريكيين الذين كتبوا روايات خيال علمي، بينما هذا النوع الأدبي يصف التصادف بِ والتعارف مع ‘الآخر الغريب’. وكتب في السنة 1993: “هل يمكن لمجموعة تم مسح ماضيها بشكل متعمَّد، والتي استهلكت طاقتها فيما بعد في البحث عن آثار واضحة لتاريخها، أن تتصور مستقبلاً ممكناً؟” الجواب على هذا السؤال هو كُثرة إنتاجات الأفروفيوترِسم منذ تلك الفترة

كثيراً ما تصنف الخيال العلمي في فئة الأفروفيوترِسم، وذكر ايضاً التشابه بين الخيال العلمي العربي الأفروفيوترِسم. الباحثة الفلسطينية لمى سليمان كتبت في السنة 2016 إن التجارب التي تناولها الأفروفيوترِسم، على سبيل المثال “أنظمة السلطة الكولونيالية، العنصرية، الإقصاء، التهجير، و الهويات الجماعية للضحوية” تتعلق بالتجربة الفلسطينية. ولكنها تضيف إنه “في الوقت نفسه يجدر النظر الى السرديات الفلسطينية عن الفقدان، التهجير والنكبة كجزء من سردية عربية أوسع، ومن منظور عربي شامل.”

في بيان/مانيفستو من السنة 2015 بالعنوان “إلى مانيفستو محتمل: اقتراح فيوتورِسم عربي/ فيوتورِسمات عربية (حوار أ.)”، إقترح الفنان الأردني المقيم في إسكتلندا، سليمان مجالي، تعريف الفيوتورِسم العربي كتأمل يعيد تعريف وتمثيل العالم العربي. يقول المانيفستو: “الفيوتورِسم العربي هو إعادة النظر في وإستجواب السرد حول بحار من الخيال التاريخي.”

وهناك أيضاً دعوات لفئة نوعية خاصة للخيال العلمي من القارة الإفريقية، فئة مستقلة عن الأفروفيوتورِسم. الروائية من جنوب إفريقيا، موهاليه ناشيغو، كتبت في مقدمة مجموعتها القصصية القصيرة بعنوان “الدخلاء”، (2018): “نحتاج مشروعاً يتنبأ (لأنه بالنهاية خيال) مستقبل إفريقيا ما بعد الاستعمار، وهذا مختلف في كل بلدان القارة لأنّ الإستعمار (والفصل العنصري) أثّر فينا بشكل فريد، ولكن أيضاً متشابه” وهذا أدى إلى ما يُسمى “الفيوتورِسم الإفريقي”، الذي صكّته الروائية الأمريكية النيجيرية ننيدي أُكورِفور في السنة 2019

إستعادة الماضي

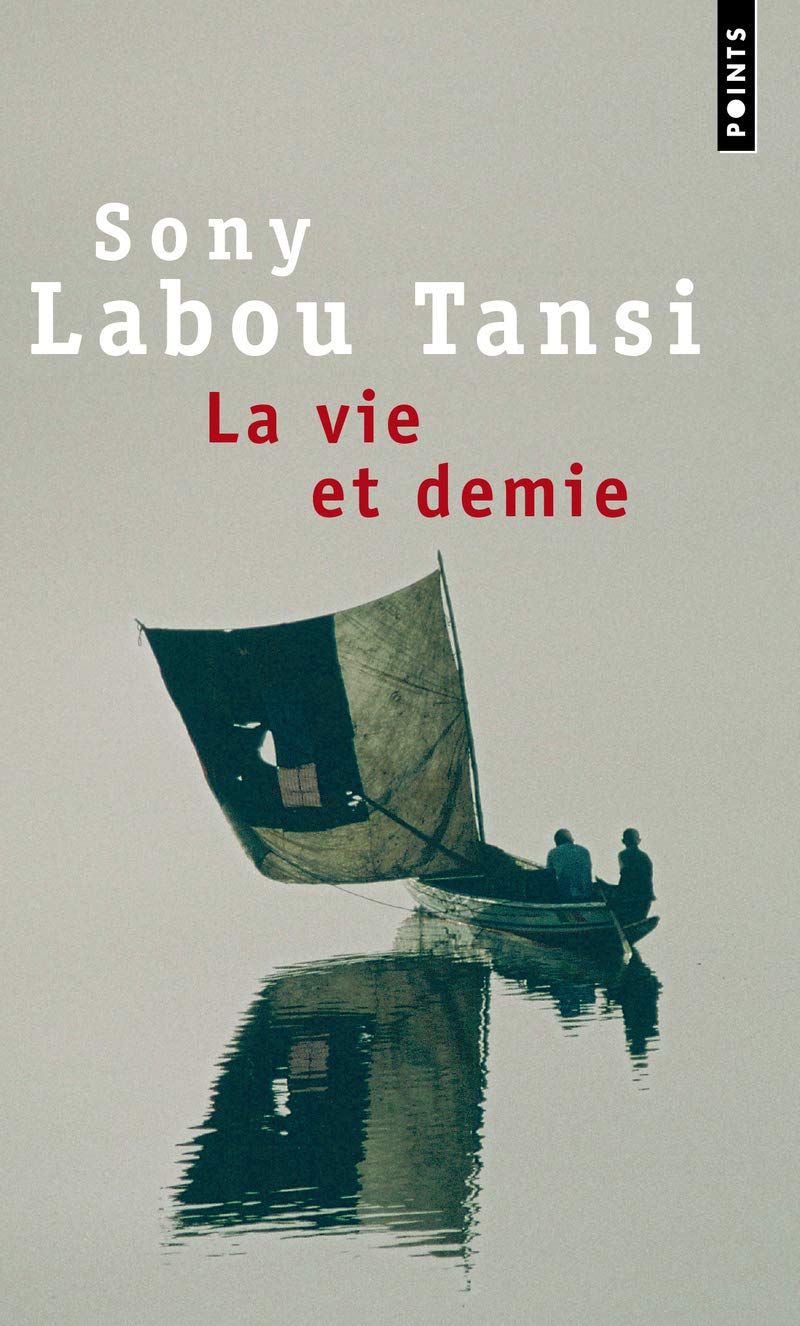

الباحثة ليدي مودِلينو وصفت في السنة 2020 الرواية “حياة ونصف” (1979) للروائي الكونغولي سوني لَبو تَنسي، بأنها ما بين الواقعية السحرية والخيال العلمي وبأنها تحقق تمثيلاً جديد لتاريخِية القارة الأفريقيا. يستعيد هذا التمثيل الجديد الماضي الإفريقي وفي نفس الوقت يضع القارة في إطار مستقبلي وبذلك يتصور المستقبل الذي، بالنسبة لأفريقيا، نكره الفلاسفة الغربيين (خصوصاً الفيلسوف الألماني هيجل)، وعرقلته الإستعمار، واعتقاله الأنظمة الدكتاتورية المتتالية

إذاً، مثل تجربة الأفارقة الأمريكيين، تمّ تنكير الهوية وتصورات عن المستقبل في البلدان العربية والإفريقية، إما من قبل أنواع مختلفة من الإستعمار أو الأنظمة المستبدة أو الحروب المدمرة. لذا، يمكن القول إن كثيراً من الطاقة أُستهلكت لتصوير النفس بعيداً عن الإنقطاعات التاريخية هذه والتأمل فيها. الخيال العلمي العربي والإفريقي يتضمن آثاراً تاريخية من خلال المرجعيات التاريخية والثقافية في قصصه

ننيدي أُكورِفور كتبت إن الفيوتورِسم الإفريقي متجذر في الثقافة، والأساطير، والرؤية الإفريقية و تاريخها. في روايتها “من يخشى الموت” (2010)، التي تروي قصة امرأة شابة في إفريقيا ما بعد حرب مدمرة، تكتشف أنّ لديها قوىً خاصة يمكن أن تمنع الإبادة الجماعية لشعوبها. تشير الكاتبة إلى المعتقدات التقليدية لشعب الإيغبو النيجيري. الكاتب الأوغندي دلمان ديلة يذكر في السنة 2015 في مقالته بالعنوان: هل الخيال العلمي فعلاً غريب عن إفريقيا؟، أمثلة لحكايات شعبية من شعب الأتشولية في أوغاندا التي تصف تقنية يمكن استخدامها في قصص الخيال العلمي

Kenyan artist Jacque Njeri imagines the Maasai in space in her series MaaSci. Source: www.Instagram.com/of_njeri

الفنانة الكنية تتصور الماساي في الفضاء. المصدر إنستاغرام

وبالنسبة للخيال العلمي العربي، ذكرت الباحثة أدا بَربَرو إنه يستند على الأدب العربي الكلاسيكي مثل أعمال أدبية فلسفية ويوتوبيا، مثل “المدينة الفاضلة” للفارابي، بالإضافة إلى حكايات شعبية. هناك وصفات لتقنيات متقدمة في عدة قصص “ألف ليلة وليلة”، على سبيل المثال قصة “حصان الأبنوس”، حول حصان ميكانيكي متحرك يطير إلى الفضاء الخارجي نحو الشمس. وتذكر بَربَرو أيضاً أدب العجائب، الذي يصف ظواهر حقيقية أو خيالية تحدى الفهم الإنساني

تصوير المستقبل العربي والإفريقي

في تصور المستقبل، كما هو متوقع في الخيال العلمي، تلعب التقنية دوراً مهماً. أحياناً تُصور التقنية كآلة لقمع المواطنين أو للتلاعب والسيطرة على أجسادهم، وهما موضوعان معروفان في الخيال العلمي. في بعض أعمال الخيال العلمي العربي والإفريقي، هذه التقنية الديستوبيا لديها دلالات تاريخية. في كتابه من السنة 2018 بالعنوان “الخيال العلمي العربي”، يقول الباحث إيان كامبيل إن التقنية في الخيال العلمي العربي متعلقة بانقطاع “التطورات الماضية وركود الحاضر”، بالإضافة إلى التوتر بين التحديث التكنولوجي واستخدام التكنولوجيا كوسيلة أجنبية (غربية) لِلا إنسانية (أو نزع إنسانية) الشعوب في البلدان العربية

أمثلة لذلك قصة سليم حدّاد القصيرة “أغنية العصافير” التي نشرت في مجموعة قصص قصيرة “فلسطين +100”. تتخيل قصص هذه المجموعة فلسطين مئة سنة ما بعد نكبة 1948، عندما طردت إسرائيل الآلاف من الفلسطينيين. تركز قصة حدّاد على بنت سُجنت مع بقية الفلسطينيين في محاكاة افتراضية. أخوها، الذي إستطاع الفرار، يقول لها: “نحن الجيل الأول الذي عاش حياته بشكل كامل في المحاكاة. نحن على جبهة شكل جديد من الاستعمار. ولذا، علينا أن نُطَوِّر شكلاً جديداً من المقاومة.”

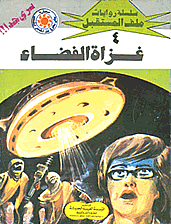

ولكن، أعمال خيال علمي أدبية أخرى تتصوّر التقنية كقوة للتمكين وتدعو إلى إستخدامها، أو على الأقل قبولها الجزئي. مثال لذلك، سلسلة متخصصة من أدب الخيال العلمي كتبها الدكتور المصري نبيل فاروق بالعنوان “ملف المستقبل” يشمل أكثر من مئة كتاب و يدور حول فرقة محققين عالميين من ‘القيادة العليا للاستخبارات العلمية المصرية’. عندما احتلت في السلسلة مجموعة من الكائنات الفضائية العالم ودمرت التطورات العلمية، تستطيع الفرقة أن تستعيد الأرض وتصبح مصر الرائد العالمي في المجال التكنولوجي والعلمي

من المواضيع الأخرى التي يتناولها الخيال العلمي العربي والإفريقي التغيير المناخي، والهجرة، والتوسع الحضري، والدين. الرواية “رجل تحت الصفر” (1965) للكاتب المصري مصطفى محمود مثال لهذا الأخير. شخصيتها الرئيسية هو استاذ يتنبأ أن الإنسان في مصر المستقبلية لن تحصل على الخلاص إلّا بالإيمان. الرواية مثال لما سمّاه الباحث روفين سنير في السنة 2000 “الخيال العلمي الإسلامي“.

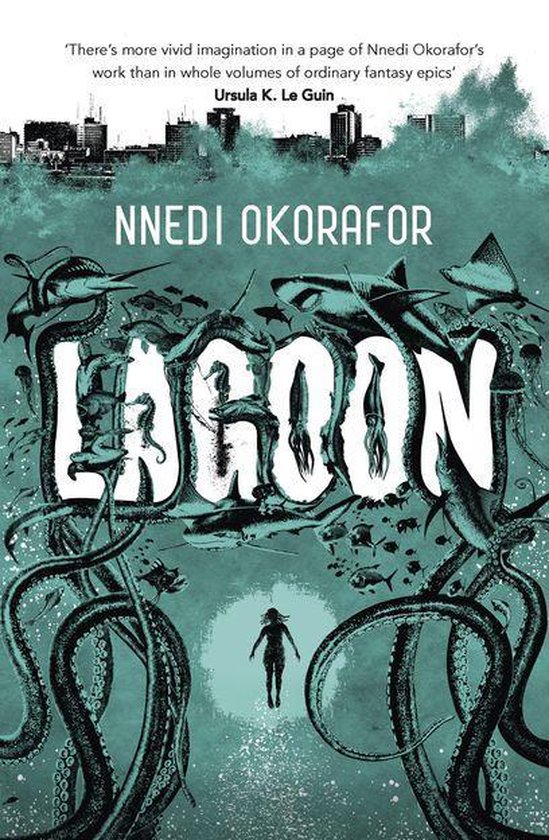

مثال الرواية التي تركز على التدهور البيئي هي “لاغون” (2014) للكاتبة ننيدي أُكورَفور المذكورة أعلاه. هبطت فيها مجموعة من الكائنات الفضائية في المحيط القريب من مدينة لاغوس في نيجيريا، حيث يريدون أن ينظفوا المياه الملوّثة. تستدعي الكائنات الفضائية مساعدة ثلاثة أشخاص يجعلون من نيجيريا اوتوبياً ما بعد النفط. ولكن تمّ تحدي جهودهم من قبل مواطني لاغوس، الذين يريدون أن يستخدموا الكائنات الفضائية لأهدافهم الشخصية

cover of “Lagoon”, by Nnedi Okorafor

غلاف لرواية “لاغون” لنندي أكورَفور

التأمل في الحاضر

في وصفها للمستقبل يتأمل الخيال العلمي في الحاضر بأن يكبّر عناصر معينة من الواقعة الحالية، سواء كان البعد الإجتماعي أو السياسي أو البيئي أو التكنولوجي. استخدام الخيال العلمي من قبل الكتّاب العرب والأفارقة لانتقاد ظروفهم الإجتماعية والسياسية والإقتصادية وواقعية الظروف الإقليمية والدولية الأخرى، من ضمنها الأنظمة الاستبدادية والتدخلات الأجنبية المدمرة من وقت الإستعمار إلى تدخلات الوقت الحاضر

في البلدان حيث يواجه الكتاب الرقابة والسجن وحتى التعذيب، يُوفر غموض الخيال العلمي وسيلة لإخفاء الانتقادات السياسية والإجتماعية وإمكانية لإنكار هذه الإنتقادات. قال روائي الخيال العلمي المصري أحمد خالد توفيق، إن كتابة الخيال العلمي بالنسبة له وسيلة أمنية للتعبير عن آرائه بدون أن يُعتبر ضد الحكومة، ولذلك يستطيع تجنّب الرقابة

رواية توفيق “اوتوبيا” (2008)، تدور أحداثها في مصر في السنة 2033 عندما يكون المجتمع منقسماً إلى قسمين: أوتوبيا التي تتمتع بحماية جنود البحرية، وبلد الفقراء الآخرين. كنوع من طقوس المرور، تخرج الشخصية الرئيسية من اوتوبيا لصيد وقتل أحد الفقراء، ولكنه لا يستطيع أن يرجع. ‘جابر’، من أرض الفقراء، يساعده. مع انتقادها للفساد وعدم المساواة بين الطبقات، توصف هذه الرواية بأنها تتأمل في الوضع الذي أدى إلى ثورة 25 يناير في السنة 2011 وتظهر كيف يُمكن لمظاهرات أن تؤدي إلى تعزيز سلطة الأنظمة الدكتاتورية

تدور الرواية الكونغولية المذكورة أعلاه، “حياة ونصف” لتانسي، في البلد المتخيلة كاتاملاناسيا، حيث تمّ إغتيال ‘مرتِيال’، وهو قائد المقاومة ضد المستبد القاتل واسمه ‘الدليل العجيب’. تتراكم الأحداث التي تعقِب القتل إلى حرب كارثية يقاتل الأطراف فيها بأسلحة متطورة علمياً مثل الذباب المعدل جينيا. تستخدم الرواية عناصر من الخيال العلمي لإنتقاد الدكتاتوريات الديستوبية المستبدة في الكونغو مثل دكتاتورية موبوتو. من خلال العناصر غير الواقعية، استطاع الكاتب تانسي أن يتجنب الرقابة، واصرّ إن روايته خرافة لانه لم يكن لديه الفرصة للكتابة عن أحداث حقيقية.

الحروب في العالم العربي كثيراً ما توصف عبر قصص ديستوبية. في رواية “حرب الكلب الثانية” (2018) للكاتب الأردني الفلسطيني إبراهيم نصر الله، اندلعت حرب مدمرة عندما يبدأ المواطنون في بلد لم يذكر إسمه بالتشابه من بعضهم البعض. وممكن قراءة هذا كتحذير من فقدان الهوية العربية في ضوء العولمة، أو دعوة الأجيال المستقبلية للإحتفال بتقاليدهم وثقافتهم، أو تحذير من إستمرار الحروب التي تؤدي إلى فناء العالم العربي بسبب خسارة الأرواح

مجموعة قصص قصيرة “العراق +100” مثال لخيال علمي ينتقد التدخل الأجنبي، فقصصها من كتاب عراقيين مختلفين تصف حالة العراق في السنة 2103، يعني مئة سنة بعد غزو العراق المدمر بقيادة أمريكا الذي من بين تبعاته الأخرى أدى إلى زيادة الصراعات الطائفية. في القصة “العامل” لضياء جبيلي، يقلل الحاكم الثيوقراطي المستبد لمدينة البصرة من قسوة الوضع المأساوي للمدينة بالإشارة إلى الأحداث التاريخية، مما يفرض على المواطنين الجائعين نزعة أخلاقية ضارة. يقول للمواطنين: “هل وصل أي منكم إلى النقطة التي يشعر فيها بالجوع بما يكفي لسرقة الأطفال وطهي لحمهم وبيع ما تبقى للجياع بسعر مخفض؟ لذلك أنصحكم جميعاً بالنظر حولكم وعدم الشكوى “.

استنتاج

تفاعلت روايات الخيال العلمي من أجزاء مختلفة من العالم، وألهمت بعضها البعض وتطورت بالتوازي، على الرغم من بقاء الخيال العلمي الغربي هو الأكثر هيمنة. تهدف هذه المقالة إلى إظهار أن الخيال العلمي قابل للتكيّف للسياق الثقافي أو التاريخي أو المستقبلي الذي يمثله. توفر الجودة الغامضة للخيال العلمي، وغموضه، والطبيعة التأملية لكتاب الخيال العلمي وسيلة لاستعادة الماضي، وتصور المستقبل، وانتقاد الحاضر وفي نفس الوقت طرح أسئلة حول ما يعنيه أن تكون إنساناً. بينما ركزت هذه المقالة على الخيال العلمي العربي والأفريقي، فإنها تُقر بوجود تنوع كبير داخل هاتين المنطقتين المتداخلتين جغرافياً. هذا، بالإضافة إلى أهداف الخيال العلمي المشتركة، يدعو إلى دراسات أكثر تفصيلاً عن الخيال العلمي العربي والأفريقي، و الفيوتورِسم العربي والفيوتورِسم الإفريقي في مجالات فنية مختلفة مثل الفن التشكيلية والعمارة و الموسيقى في المستقبل.

تابعوا ديسيري على تويتر @desicusters

Arab and African Science Fiction: (re)claiming the past, reflecting on the present, and envisioning the future

Introduction

Though fervent readers of science fiction (SF) will already be familiar with SF from the Arab and African regions, it remains underexplored for many readers and writers of the world. This despite the fact that Arab and African SF works having been published since the start of the previous century

And though the two regions are often artificially divided in the social and political sciences as well as literary studies, they have much in common, similarities which are translated in their SF. Using broad strokes, this essay will show that Arab and African SF literature has three common functions: it envisions the future, reclaims the past, and reflects on the present

SF as a genre

Science fiction (SF), I believe, is one of the most effective literary genres to shape and express our imagination of the future. Its odd narratives achieve cognitive estrangement by being set in an alternative or altered reality and by describing circumstances that go beyond the confines of the normal human experience

In doing so, SF addresses philosophical questions on what it means to be human: as an individual, as a society, as a religious being and as related to the environment and technology. Over the years different subgenres have developed within SF, including Afrofuturism, Feminist SF, and Arab- and Africanfuturism, the latter two of which this essay will see as included in the definition of Arab and African SF

Nigerian artist Abass Kelani probes the relation between man and machine in his artwork. Source: Omenka Gallery

الفنان النيجيري عباس كيلاني يستكشف العلاقة بين الإنسان والنكنولوجية في أعماله الفنية. مصدر: معرض أومنكا

An own SF

When in 1993 author and culture critic Mark Dery coined the term ‘Afrofuturism’ (which explores intersections of blackness, race, speculative fiction, technology and the future), he wondered why few African Americans wrote SF while it was par excellence the genre that described encounters with the ‘stranger Other’. He asked: “can a community whose past has deliberately rubbed out, and whose energies have subsequently been consumed by the search for legible traces of its history, imagine possible futures?” A clear answer to this question is the fact that Afrofuturism has come to include a vast tradition

African SF has often been categorized as Afrofuturism, and it’s overlap in themes with Arab SF have also not remained unnoticed. Palestinian researcher Lama Sulaiman writes in 2016 that the experiences Afrofuturism discusses, such as “power regimes of colonialism, racism, marginalization, displacement, and collective identities of self-victimization”, relate to the Palestinian experience. Yet she adds that Palestinian narratives of loss, dispossession, and catastrophe have to be seen as part of wider Arab narratives and from within a Pan-Arabist perspective

In a 2015 manifesto entitled Towards a possible manifesto; proposing Arabfuturism/s (Conversation A), Jordanian artist Sulaiman Majali, who lives in Scotland, writes: “-Arabfuturism is a re-examination and interrogation of narratives that surround oceans of historical fiction.” His manifesto thus suggests framing Arabfuturism as a reflection that redefines representations of the Arab world

There have also calls for a seperate category of SF that is specific to the African continent, away from the Afrofuturist tradition. South African novelist Mohale Mashigo wrote in the preface to her short story collection Intruders (2018): “we need a project that predicts (it is fiction after all) Africa’s future ‘postcolonialism’; this will be divergent for each country on the continent because colonialism (and apartheid) affected us in unique (but sometimes similar) ways.” This resulted in the term ‘Africanfuturism’, coined by Nigerian-American fiction writer Nnedi Okorafor in 2019

Reclaiming the Past

Researcher Lydie Moudileno in 2020 describes the novel La Vie et Demie (1979, English trans. Life and a Half,2011) by Congolese novelist Sony Labou Tansi, as a hybrid of magic-realism SF that “achieves a new representation of African historicity which not only reclaims the past, but also projects the continent into the future, a future which, in the case of Africa, has been famously denied by Western philosophy (most notoriously Hegel), impeded by colonization and arrested by successive dictatorial regimes”

Like the African American experience, identity and visions of the future in the Arab and African regions have been denied, either by different shades of colonisation or by authoritarian regimes and all-encompassing conflicts. Thus, one could argue that much energy is consumed by reimagining of the self away from these historical disruptions and reflection on these disruptions. Importantly, African and Arab SF actively includes traces of history through cultural and historical references

Nnedi Okorafor writes that Africanfuturism is rooted in African culture, history, mythology and point-of-view. In her novel Who Fears Death (2010), in which a young woman in postapocalyptic Africa discovers special powers that can prevent the genocide of her people, the author refers to Igbo traditional beliefs. Ugandan writer Dilman Dila in his 2015 blogpost Is Science Fiction Really Alien to Africa?, mentions examples Acholi folk tales that feature technology and can be used in SF writing

In the Arab case, researcher Ada Barbaro has described how modern Arab SF makes use of classical Arabic literature such as philosophical and utopian works, but also folktales. The tales of 1001 Nights, for example, depict advanced technologies. One such tale is ‘The Ebony Horse’, a story about a mechanical horse that can fly to outer space to the sun. Barbaro also mentions aja’ib (‘marvels’) literature, which emphasises real or imaginary phenomena that challenge human understanding

Imagining the Arab and African Future

In imagining the future, as expected in SF, technology plays an important role. It is sometimes portrayed as a tool to oppress populations or to manipulate and control their body, two familiar tropes in SF. Some examples of African and Arab SF depict this dystopian technology based on historical connotations. Ian Campbell in his 2018 book Arabic Science Fiction, argues that technology in Arab SF relates both to the discontinuity between “past progress and current stagnation” as well as tensions between technological modernization and technology as a dehumanizing foreign (Western) tool

An example can be found in Saleem Haddad’s ‘Song of the Birds’ in the short story collection Palestine +100,which imagines Palestine hundred years after the Nakbah (‘catastrophe’) of 1948, when the state Israel was declared and hundreds of thousands of Palestinians were uprooted. It centres a young girl who, along with all other Palestinians, is imprisoned in a virtual simulation. Her brother, who managed to escape, tells her: “we are the first generation to have lived our entire lives in the simulation. We are at the frontier of a new form of colonisation. So it’s up to us to develop new forms of resistance”

However, other SF works frame technology as an empowering tool and advocate for its development, or at least partial embrace. Egyptian Nabil Farouk’s detective-SF series titled Milaff al-Mustaqbal (‘The future file’, 1980s), for example (which includes more than 100 books) depicts the crew of scientists of the ‘High Command of Egyptian Scientific Intelligence’. When in the series earth is occupied by alien warriors who destroy the planet’s scientific developments, the team manages to regain earth and Egypt becomes the world’s leader in science and technology

Example of one of the Milaff al-Mustaqbal

أحد كتب ملف المستقبل

Topics discussed in Arab and African SF also include questions of environmental change, migration, urbanization and religion. Rajul Taht al-Sifr (‘The man with a temperature below zero’, 1965) by the Egyptian Mustafa Mahmoud is an example of this latter. It’s main character, a professor, predicts Egypt’s future as one in which human life is controlled by materialistic interests. The novel forecasts that people will only be able to turn to God for redemption. It is one example of what Reuven Snir in 2000 called Islamic science fiction

An example of a novel that, among others, addresses environmental degradation is Lagoon (2014) by the earlier mentioned Nnedi Okorafor. In it, aliens have landed in the ocean near Lagos, Nigeria, where they plan to clean up the polluted water. They seek collaboration with three human protagonists to work towards a post-petroleum, utopian Nigeria. But their efforts are challenged by the citizens of Lagos, many of whom plan to use the aliens for their own agenda

Reflecting on the Present

In describing the future, SF reflects on the present by enlarging certain aspects of current reality, whether social, political, environmental or technological. It has been used by African and Arab authors to criticize social, political and economic and other regional and global realities, including authoritarian regimes and disruptive foreign intrusions from the colonial times to modern-day interferences

In countries where writers face censorship, imprisonment and even torture, the ambiguity of SF offers writers the benefit of concealing social and political critique and providing plausible deniability when confronted with scrutiny. Egyptian SF writer Ahmed Khaled Tawfik, for example, once said that writing SF was a safe way for him to express his opinions without being considered against the government and allowed him to escape censorship

Tawfik’s 2008 novel Ūtūbīa (English trans. Utopia, 2012) is set in 2023 Egypt where society is divided in two separate territories: the marine-protected land of the rich, Utopia; and the land of the poor ‘Others’. As a rite of passage, the protagonist leaves Utopia to hunt and kill an ‘Other’. However, he gets stuck, and it is Gaber, from the land of the poor, who protects him. Criticizing class inequality and corruption, the novel is described as reflecting on the conditions leading to the uprisings in 2011 and showing how such protests lead to a further consolidation of power by the authoritarian regimes

The earlier-mentioned novel Life and a Half by Tansi is set in the fictional republic of Katamalanasia, where Martial, leader of the resistance to a murderous dictator called the Providential Guide, is killed. The events that follow cumulate into an apocalyptic war that is fought with super science weapons such as mutant flies. The novel uses elements of SF to criticize dystopian dictatorial powers in Congo akin to the Mobutu era. Using elements outside the realm of reality, Tansi was able to outmaneuver official censorship. He has insisted that his book was a fable because he did not have the opportunity to write about real events

Cover of “Life and a Half” by Sony Labou Tansi

غلاف لروياة “حياة ونسف” لسوني لَبو تَنسي

Present-day conflict in the Arab world is often reflected in dystopian SF works. In the novel Harb al-Kalb al-Thaniyah (‘The Second Dog War’, 2018) by Jordanian/ Palestinian writer Ibrahim Nasrallah, a dystopian war breaks out when citizens of an unnamed country start to look alike. This metaphor can be read as a warning against the increased loss of authenticity in an ever-globalizing world, a call for future generations to celebrate their traditions and culture, or a warning against the continuation of conflicts that leads to the annihilation of the Arab world through the loss of lives

Iraq +100 (2017) offers an example of SF criticizing foreign intervention. In the collection of ten short stories different Iraqi writers describe their country in 2103, 100 years after the US-led invasion which had devastating consequences such as increased sectarianism. In the story ‘The Worker’ by Diaa Jubaili, the tyrannical theocrat ruler of the city Basra downplays the city’s dire situation by referring to historical events, forcing on the starving citizens a perverse moral relativism: “Have any of you reached the point where you’re hungry enough to steal children, cook their flesh, and sell what’s left to the starving at a discount? I therefore advise you all to look around and not complain

Conclusion

SF novels from different parts of the world have interacted, inspired each other and developed in parallel, despite the Western tradition remaining the most dominant. This essay aimed to show that SF is mouldable to the cultural, historical or future context that it represents. SF’s estranging quality, ambiguity and speculative nature offer authors a medium to reclaiming the past, imagining the future, and criticizing the present while asking questions on what it means to be human. While this essay focused on Arab and African SF, it acknowledges that within these geographically overlapping regions there is great diversity. This, combined with their shared functions of SF, invites to more detailed studies of Arab and African SF and Arab- and African futurism in the future, including in the field of arts, architecture, and music

Desiree tweets via @desicusters

Another collage by artist Ayham Jabr. Source: Pinterest

كولاج للفنان أيهك جبر. مصدر: بينتريست

A very expansive collection of SF since I read about the Second Dog War from you!! Want to grab an arab/african SF and read NOW!!

إعجابإعجاب

Mandymui, this is the greatest comment I could have ever wished for! Thank you so much!

إعجابإعجاب